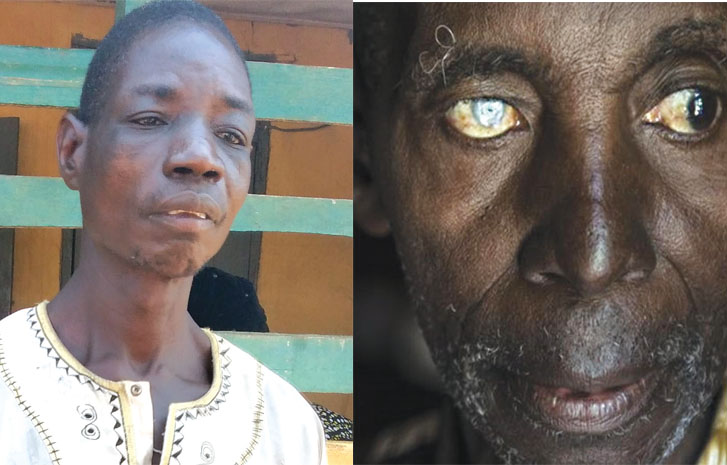

Nigeria Faces Ongoing Challenges in Combating River Blindness

River blindness, also known as onchocerciasis, is a serious neglected tropical disease that affects millions of people globally. Caused by the parasite Onchocerca volvulus, it is transmitted through the bite of blackflies, which breed in fast-flowing rivers and streams. The disease is particularly prevalent in rural areas, where poor environmental conditions often exacerbate its spread.

According to global health data, more than 99% of infected individuals live in Africa and Yemen, with the remaining 1% found along the border between Brazil and Venezuela. In 2023, at least 249.5 million people worldwide required preventive treatment against onchocerciasis. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that in 2017, 14.6 million people had skin disease caused by the infection, while 1.15 million experienced vision loss.

In Nigeria, researchers from the Nigerian Institute of Medical Research have highlighted the significant risk posed by river blindness. Dr. Babatunde Adewale, a Director of Research at the institute and a Public Health Parasitologist, noted that 43 million Nigerians are currently at risk of contracting the disease. He emphasized that although many communities have been receiving treatment for years, challenges such as insecurity and limited access to healthcare continue to hinder progress in some regions.

The drug ivermectin has proven effective in targeting the larvae of the parasite, but adult worms remain a challenge. These worms can live for several years and continuously produce microfilariae, making long-term and consistent treatment essential to interrupt the transmission cycle.

Adewale explained that Nigeria is now in the stage of transmission interruption, thanks to sustained mass treatment efforts. He pointed out that 37 million people have already received treatment, and in some areas, the program has been scaled down. However, ongoing efforts are still necessary in regions affected by insecurity, where it is difficult for health teams to reach vulnerable populations.

He listed several states where transmission interruption has been achieved, including Katsina, Nasarawa, Enugu, Anambra, Borno, and Abia. Ongoing laboratory analysis of over 3,000 blood samples per location is helping the Federal Ministry of Health determine which states are nearing elimination thresholds. According to Adewale, if the positivity rate in a state is found to be less than 0.1%, it is considered that transmission has been interrupted.

Adewale expressed optimism about Nigeria’s ability to achieve elimination status by 2030. He stated that the national target is to eliminate the disease by that year, and he believes the country is on track to meet this goal. He emphasized that ivermectin is highly effective, with studies showing that after six months of treatment, microfilariae may no longer be detectable in the skin. However, he noted that eliminating the disease requires long-term use of the drug, as adult worms can take years to die off.

Sociocultural Barriers to Effective Treatment

Dr. Adeniyi Adeleye, a medical sociologist and research fellow at NIMR, highlighted another critical challenge: local beliefs that hinder the acceptance of medical interventions. Many people in rural communities, where the disease is most common, do not associate river blindness with insect bites, despite scientific evidence linking the condition to blackfly bites.

Adeleye cited findings from community-based research that revealed many affected populations attribute the disease to supernatural causes such as witchcraft or divine punishment. These misconceptions create barriers to the adoption of medical treatments and public health initiatives. He stressed that addressing these sociocultural factors is essential to ensure that innovations and treatments for onchocerciasis are both available and understood by those who need them most.

Public health efforts must bridge the gap between scientific knowledge and local realities to make meaningful progress in the fight against river blindness. This includes education, community engagement, and culturally sensitive communication strategies to foster trust and encourage participation in treatment programs.