-

READ MORE: Urgent warning to Just Eat customers over scam listings

If you use apps such as Deliveroo and

Uber

, you might want to think twice about giving the delivery driver a hard time.

A new study by scientists at the

University of Cambridge

lays bear the misery of being a food delivery worker or ride-hailing driver in Britain.

More than two-thirds of riders and drivers in UK’s ‘gig economy’ suffer anxiety over long hours and bad ratings, the experts report.

Tolong support kita ya,

Cukup klik ini aja: https://indonesiacrowd.com/support-bonus/

Meanwhile, three-quarters have anxiety over fears that their pay – typically below the UK minimum wage – is going to fall.

Lead study author Dr Alex Wood from Cambridge’s Department of Sociology said riders and drivers ‘have little in the way of rights or bargaining power’.

‘Delivery and ride-hailing platforms combine manual work with tight algorithmic management and digital surveillance,’ he said.

‘Platform companies call themselves tech firms, but in practice they govern, control and profit from labour they claim not to own, without bearing employer responsibility.

‘If your job is at the mercy of a quick click on a stranger’s phone, it is likely to fuel a constant hum of uncertainty and anxiety, along with feelings of being judged, monitored and replaceable.’

The study focused on job quality in the UK’s ‘gig economy’ – the labour market characterised by short-term contracts or freelance work, rather than permanent jobs.

Gig economy workers operate as self-employed contractors who sign up for work on digital platforms such as Uber, Deliveroo, Amazon Flex and Upwork.

These digital platforms typically match the workers with customers and pay a base rate per job, with higher rates at peak times or ‘surges’.

‘All manner of gig work has exploded in recent years, from delivering food to building websites,’ said Dr Wood.

‘Many of us now summon people and labour at the tap of a smartphone screen without much thought, rarely considering the process or the people behind it.’

Between March and June 2022, Dr Wood and colleagues surveyed 510 gig economy workers in the UK about different feelings towards their role.

Of the total, 257 were defined as ‘local’ platform workers – those tied to locations such as delivery riders for the likes of Deliveroo, Uber and Amazon Flex.

The remaining 253 were ‘remote’ platform workers – whose labour is digital and so can remote work from anywhere, on platforms like Upwork and Fiverr.

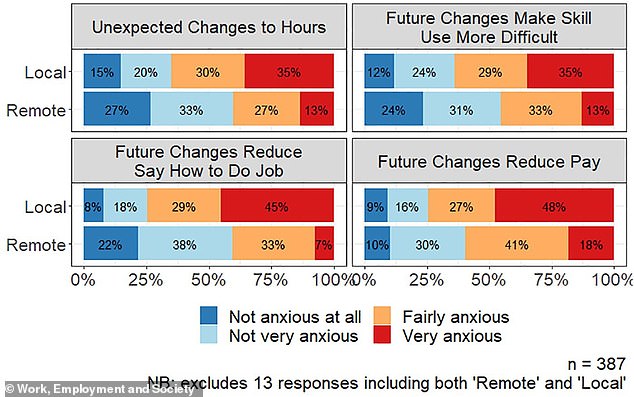

In all, 65 per cent of local workers reported feeling either ‘fairly anxious’ or ‘very anxious’ about future unexpected changes to working hours, compared with 40 per cent for remote workers.

An even greater proportion of local workers – 74 per cent – were at all anxious about having less say over how their job is done, compared with 40 per cent for remote workers.

Also, more local workers reported anxiety over the potential for pay to fall (75 per cent compared to 59 per cent of remote workers).

And 64 per cent were anxious about it becoming more difficult for them to use their skills going forward – due to the fear of automation, for example – compared with 46 per cent for remote.

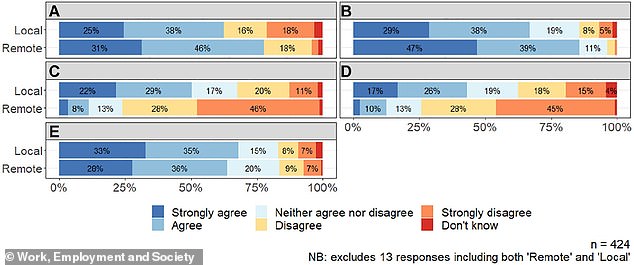

Another part of the research uncovered ‘very high’ levels of insecurity among respondents in terms of feeling there was a chance of losing their ability to make a living and becoming unemployed as well as other types of work-related insecurity.

For example, 68 per cent of local platform workers said they feared receiving ‘unfair feedback that impacts their future income’.

Just over half of local workers (51 per cent) said they risked physical health or safety, nearly five times higher than remote workers (11 per cent).

And 43 per cent said they suffer physical pain resulting from work, compared with about 13 per cent for remote workers.

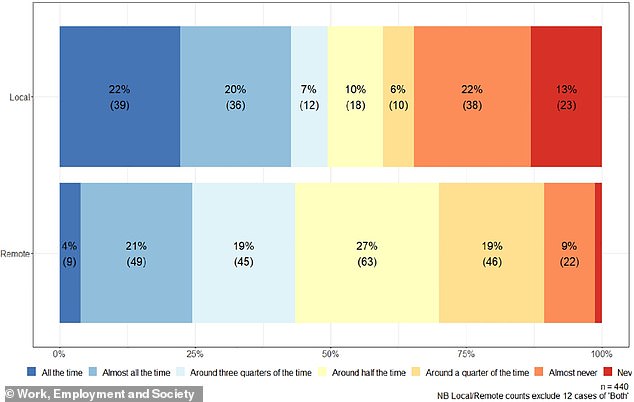

Local workers also reported spending an average of 10 hours a week waiting for jobs to come through on the app, compared with four hours for remote workers.

But regardless of how long they’re doing this for, the gig economy experience means they logged on and technically working but not making any money, according to the researchers.

However, they admit that gig economy workers have flexibility and a level of independence that permanent workers don’t get.

The study, published in the journal

Work, Employment and Society

, is the first to provide statistical data on job quality in the UK’s ‘gig economy’.

‘Attempts to investigate working conditions in the UK gig economy have been hampered by the difficulty of identifying and accessing people doing the work,’ said co-author Professor Brendan Burchell, sociologist at the University of Cambridge.

‘Classifying someone as self-employed doesn’t change the fact they can be economically dependent and exploited.’

An Uber spokesperson said: ‘More drivers and couriers are choosing to earn on Uber in the UK than ever before and we know that the vast majority are satisfied with their experience.

‘The Uber app reviews real-time information to provide the best price to appeal to the drivers or couriers in the area, helping to minimise waiting times for customers and maximise earnings.

‘We regularly engage with drivers and couriers to look at how we can improve their experience.’

A Deliveroo spokesperson said: ‘We’re proud to provide the flexible work riders repeatedly tell us they value most, along with attractive earnings opportunities, with thousands of rider applications received each week.

‘We were the first major delivery platform to enter into a voluntary partnership with the GMB Union, and have led the industry by introducing vital protections like insurance and sickness cover.

‘Deliveroo does not operate many of the features mentioned in this report. Riders are self employed, free to choose when, where and how long they work for, without any impact on future work offered through us.’

Read more