A New Perspective on the “Good Life”

For centuries, the concept of a “good life” has been defined in two primary ways: one centered on happiness, characterized by positive emotions and a sense of well-being, and another focused on meaning, which involves purpose, personal fulfillment, and a deeper sense of direction. However, new research is suggesting that there may be a third path—one that values challenge, change, and curiosity as equally important as happiness or meaning.

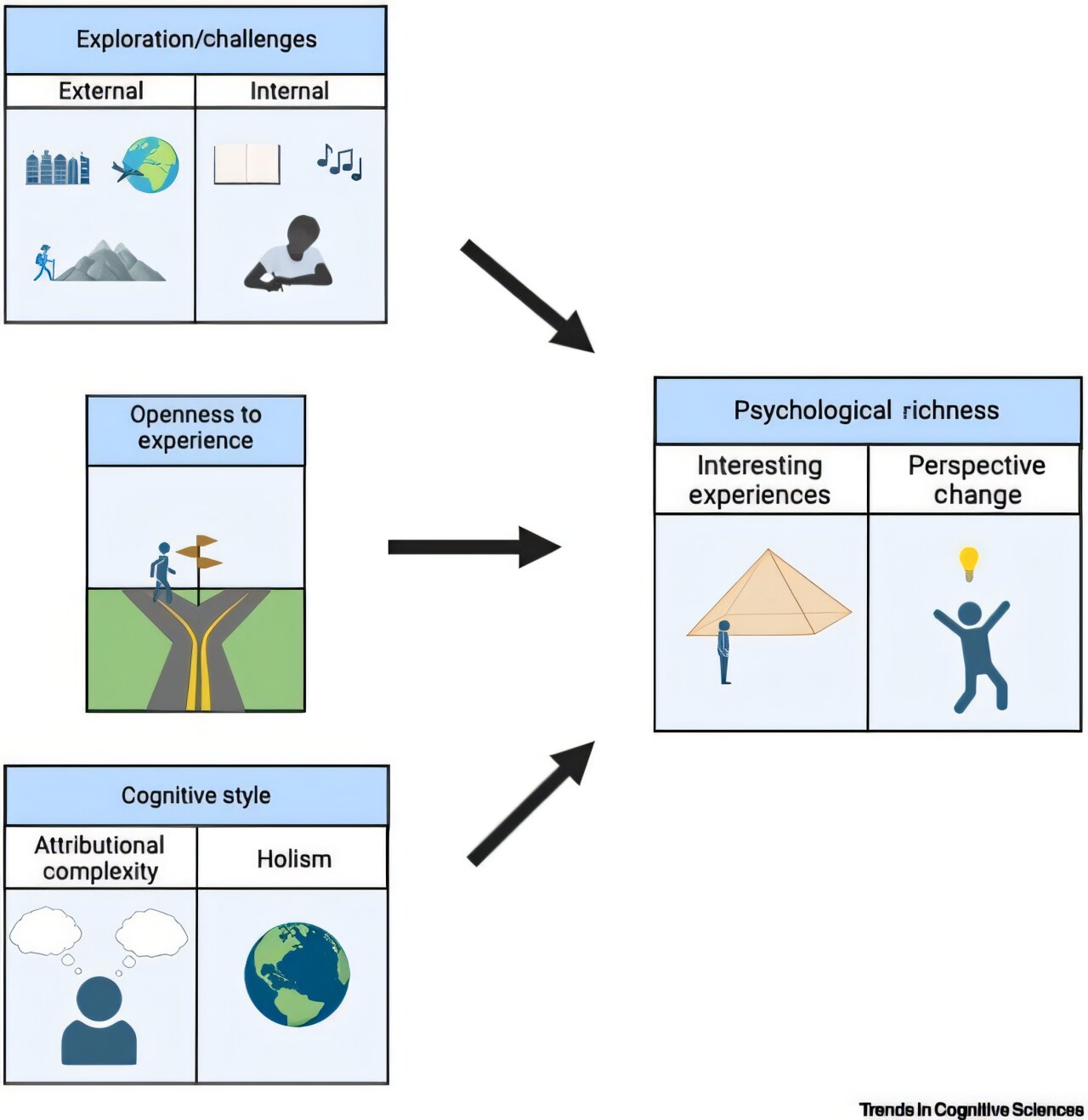

This emerging idea, known as psychological richness, is being explored in a recent study published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences. The research was led by Erin Westgate, Ph.D., a psychologist from the University of Florida, in collaboration with Shigehiro Oishi, Ph.D., from the University of Chicago. According to their findings, some individuals prioritize variety, novelty, and intellectually stimulating experiences—even if these experiences are difficult, unpleasant, or lack clear meaning.

Westgate explains that the concept originated from a simple but profound question: “Why do some people feel unfulfilled even when they have happy and meaningful lives?” Through their research, she and Oishi found that what many people were missing was psychological richness—experiences that challenge them, change their perspective, and satisfy their curiosity.

Understanding Psychological Richness

Psychological richness refers to a life filled with diverse, perspective-changing experiences. These can be external, such as traveling, learning new skills, or taking on challenging tasks, or internal, like reading a powerful book or listening to a moving piece of music. According to Westgate, such experiences don’t always need to be dramatic or exciting. Even something as simple as reading a great novel or hearing a haunting song can shift the way someone sees the world.

Unlike experiences that bring happiness or meaning, rich experiences are not always pleasant or purposeful. For example, college is often seen as an experience that isn’t always fun, nor does it always provide a clear sense of meaning. Yet, it can significantly alter how someone thinks and views the world. Similarly, living through a hurricane might not be considered a happy or meaningful event, but it can profoundly change a person’s perspective.

Westgate’s lab at the University of Florida has been studying how people respond to challenging events, including tracking students’ emotions during approaching storms. The results show that many individuals view these difficult experiences as psychologically rich, even if they didn’t enjoy them.

The Origins of the Concept

Although this study is recent, the idea of psychological richness has been developing over the years. Westgate and Oishi first introduced the term in 2022, building on earlier research from around 2015. Their latest paper expands on this concept, showing that it resonates across cultures and fills a gap in how people define well-being.

Westgate notes that for much of history, psychology and philosophy have focused on two main aspects of well-being: hedonic (happiness) and eudaimonic (meaning). However, her research suggests there is a third path—one that is just as valuable and important for some individuals.

While many people ideally want all three—happiness, meaning, and richness—there are trade-offs. Rich experiences often come at the cost of comfort or clarity. As Westgate explains, “Interesting experiences aren’t always pleasant experiences. But they’re the ones that help us grow and see the world in new ways.”

Implications for Well-Being

Westgate hopes that this research will encourage psychologists and the public to think more broadly about what it means to live a fulfilling life. She emphasizes that while happiness and meaning are still important, they should not overshadow the value of psychological richness.

“We’re not saying happiness and meaning aren’t important,” Westgate said. “They are. But we’re also saying don’t forget about richness. Some of the most important experiences in life are the ones that challenge us, that surprise us, and that make us see the world differently.”

This new understanding of well-being opens up exciting possibilities for how individuals can approach their lives, offering a broader and more nuanced definition of what it means to live well.