A Journey Through Grief and Healing

Ten years ago, I was on a holiday cruise ship in the Mediterranean when I received a call from a friend informing me that my son Jack, who was 28 at the time, had died. I remember lying on the bed in my cabin, wondering what I was going to do next. One funeral, a thousand regrets, and a million tears later, I’m still asking: what do I do now? How do you live after loss?

Jack took his own life, and with it, my old familiar life disappeared as well. Nothing would ever be the same again—or so I thought. Ten years is a good point to ask what’s changed? Is the death of a child the one wound that time can’t heal?

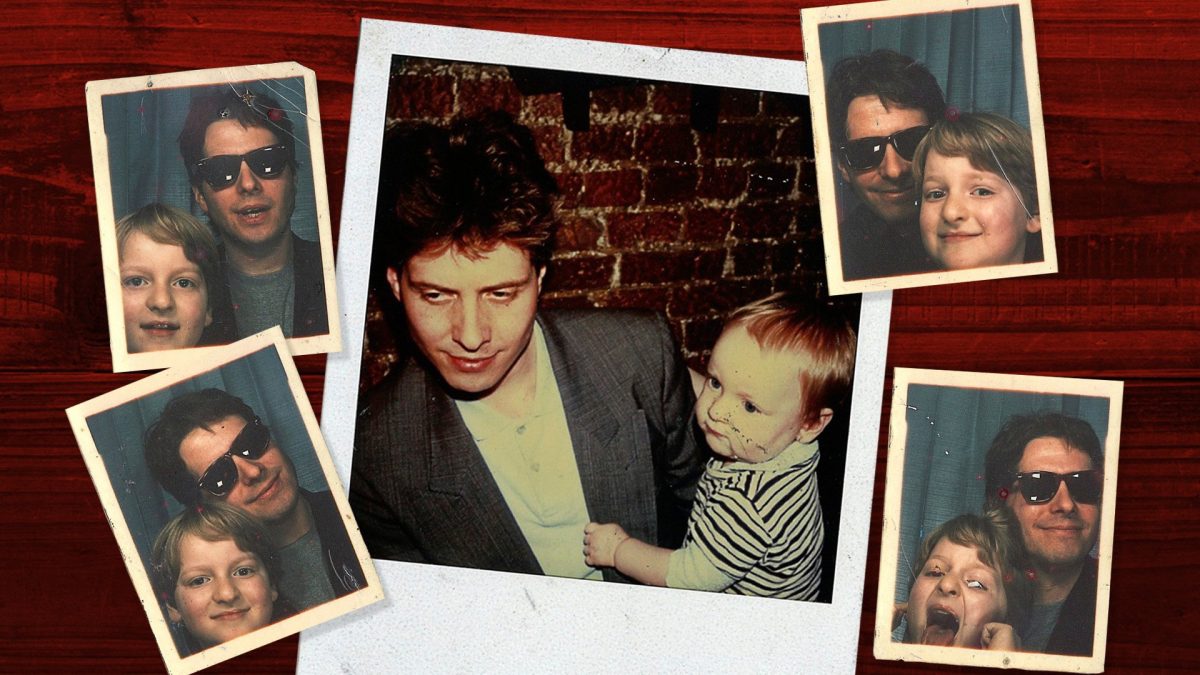

The thing about suicide is that it cancels the future with the one you have lost—and changes the past you shared together too. All your old certainties start to crack and crumble. You begin to wonder: were they ever happy? Did they hide their struggles beneath the straitjacket of a smile and silly faces for the camera?

I remember a happy six-year-old Jack and me carrying him on my shoulders, blowing loud raspberries on his belly, and bouncing him on his bed. As he entered adolescence, he seemed increasingly anxious. (His parents’ divorce hadn’t helped.) At 15, he confessed—to his best mate—that he felt frequently depressed. A few years later, I discovered that he had been self-harming.

I also discovered something else: he was using drugs. First it was mushrooms, then smoking skunk, and then MDMA, acid, and coke, and whatever was around. The first real alarm bell went off in 2005 when Jack—then 18—started hearing voices telling him he was damned and going to hell. He had a breakdown and went to the Priory.

After Jack dropped out of university around 2006—he would have panic attacks attending classes—he just gave up on making a life for himself and became one of the Lost Boys. Those young men who have so much talent, charm, and brains—and yet never miss an opportunity to screw things up.

Lost Boys like Jack go on medication, they come off medication. They go in and out of rehab, they go into therapy, they come out of therapy. They quit taking drugs, they start taking drugs. They plan to do this and they never do that. And then one day their parents get a phone call or there’s a knock at the door…

Around 2013, Jack was sofa surfing and living in squats. He was so difficult to live with that an anarchist squat in Camden Town kicked him out for bad behaviour. He got into a druggy street way of life indulging in petty theft, dealing dope, and even begging on the streets.

Towards the end of his life, he would stay with me. I remember I could hear him in the kitchen pacing back and forth in the open cage of his solitude, and every so often he uttered the cry of “Lone-leee!” Then silence. And then, “Lone-leee.”

He died a lonely death in a small room his mum and I had got for him in suburbia. The smell of his body alerted his housemates.

The big question that haunts every parent is why? Why did they do that? And the answer is never simple or straightforward as newspaper headlines suggest. The anguished mind wants answers—but till this day I have none. Just a bunch of maybes—maybe it was this and maybe it was that.

One thing I can say with certainty is that his drug use was a big factor in his decline. After one particularly bad drug binge, he said he’d “broken” his brain. It left him suffering from depersonalisation. He felt no emotion, no feelings. He couldn’t talk to anyone. He said he was a zombie. The last few months of his life, he was in a place beyond hope or help.

I did my best to save him—but my best wasn’t good enough. Was there anything I could have done to save my son? Only a hundred and one things—and yet there’s no guarantee that any of them would have worked.

In the immediate aftermath of Jack’s suicide, I read a lot about parents in my position who devoted their lives to trying to make something good out of their tragedy. They set up charities and took part in campaigns to raise public awareness—and money—around issues of mental health and suicide.

Back then, I got plenty of advice from friends and strangers on how to live after loss. I should, said one old girlfriend, join a grief support group and find “closure.” A dad told me about a book he’d read that shows you how grief is a form of growth. “Loss is a learning experience,” he assured me. And I would smile and thank these people for their concern and suggestions and think: f**k off!

I wanted nothing to do with the lot of them. I couldn’t imagine anything worse than sitting around a church hall hearing sad stories of suicide and sipping bad coffee. Or joining a bunch of dads on a walk across England to raise public awareness.

No thanks. I planned to sit in a dark room, drink, take drugs, watch daytime TV, and slowly sink into a sea of self-pity for the rest of my life—but I wrote a memoir instead called Jack and Me: Life After Loss. It was an angry nihilistic rant against our modern obsession with taking every tragedy and cleaning it up—“leaning into it” as they say—and tying up the whole nightmare experience in a pink ribbon bow of positivity.

But over time—and thanks to therapy—I began to think again. My whole suck-it-up and suffer-in-silence approach was self-defeating. I wanted to do some good for parents in my position—and most of all for myself. So I rewrote the whole book again and replaced the anger and nihilism with the kind of life-affirming positivity I once sneered at.

I thought this being the 10th anniversary of Jack’s death, it would be really hard going. My grief and guilt would return with a vengeance. I expected a day of tears and self-flagellation as I wandered through the box of old photos and played the music we played at his funeral. But it wasn’t like that. It was a calm and comforting day. I talked to my son’s urn. “Was I really such a bad dad to you?” I asked. And I could hear Jack say as he once did, “Yeah, totally!” and quickly adding, “Only kidding dad!”

After ten years, I’ve learned to live with my mistakes and let the guilt go—well, most of it. It took me years to realise that you are never the great parent you long to be—but that doesn’t make you the bad parent you think you are. You can protect your child from just about most things—except themselves.

People think that grief is something to get over, that you should find “closure.” But I don’t want that. The pain—that terrible ache of his absence—along with the love keeps me connected to my son. So you get on with your life and suddenly you step on a landmine of memory—an old picture or a piece of music pops up—and BOOM! You fall to pieces.

I had hoped that after the death of Jack I would become a different kind of man. I remember reading a writer who said that after the death of his wife he had over the years become a better man—he was kinder, calmer, a better dad and so on. That’s what I wanted too. I can only hope that I have made some small improvements over the years.

I used to sneer at the idea that loss has something to teach us about the meaning and value of life. Now I realise it can—if you let it. All the existential balls-ache and navel gazing I did for so many years about the meaning of life disappeared after Jack’s death. I discovered what it was all about: live your life with love and kindness every day. Yes, I know how trite that sounds. But every cliché is redeemed by the challenge of actually putting those words into action.

People have asked me what is the one thing I’ve learned from Jack’s death and I try to tell them this—life is fragile and anyone at any time can be taken away from you. And the one thing you will want more than anything is the one thing you can’t have: them. So I tell myself to be emotionally courageous—make sure the people you love know just how much you love them.

I swore that I would never forget Jack or what I’ve learned after his loss. But of course I do. Death wakes us up—but life puts us back to sleep. I go through long periods of not even thinking about Jack at all. The passage of time which helps us to heal also forges forgetfulness.

So what do I do now ten years after my son’s death? I try my best to keep him close and to care for the memories of our time together. I tell him: “I love you Jack” and I can hear him cringe and see him smile.

Jack and Me: One Clueless Dad, One Lost Boy by Black Spring Press. Paperback. £12.99

The Samaritans offer free support, 24 hours a day, to those struggling to cope.

Samaritans.org | call 116 123