A Life on Two Wheels

Most people who live in Edward Winterhalder’s quiet West Michigan neighborhood have never seen the cherry red Harley-Davidson motorcycle nestled under its cover in his garage. They don’t know about the 500 plus bikes he’s owned in his lifetime. They don’t know that he spent nearly 30 years riding across the continental United States as an outlaw biker, a term that typically conjures images of leather, dive bars and fist fights.

“The only perception the public has in this day and age is what they’ve seen on TV and what they’ve read about,” Winterhalder said. “Traditionally, that’s not positive in nature.”

In the past, television and other media portraying outlaw motorcycle clubs focused on the negative acts committed by a few, he said, distorting the lifestyle and not painting the entire picture. It’s a misconception the 70-year-old Hudsonville man has dedicated his life to trying to correct.

“The majority of the people involved in the lifestyle are just guilty of having too much fun on the weekends, and they’re just regular people,” he said. “It could be your neighbor.”

Winterhalder has spent over a decade working as a producer and consultant on motorcycle club-related movies and television programs, including two television series based on his own autobiography and a Biker Chicz docu-reality TV series. He’s appeared on TV shows on National Geographic and the History Channel.

Winterhalder has also authored dozens of books detailing his own experience as an outlaw biker and telling the stories of other motorcycle club members and their contributions to the culture. His most recent book, written over the span of a decade, was part of a partnership with about a dozen Grand Valley State University students who interviewed outlaw bikers and detailed their experiences.

The Beginning of a Journey

Buying his first Harley

Winterhalder’s unique life is what prompted him to begin writing about outlaw motorcycle clubs. He knows the lifestyle. He knows the people.

The term “outlaw biker” dates back to a 1947 motorcycle event in Hollister, California, he said, born from a shift away from the American Motorcycle Association (AMA), which was then a major organizing body for motorcycle manufacturers and riders.

“The AMA came out and said it’s only 1% of bikers that caused all the problems in Hollister,” Winterhalder said. “Some of the clubs at that time took that 1% moniker and ran with it. Those became outlaw bikers and outlaw motorcycle clubs.”

Winterhalder’s own experience began after he returned home from military service, quickly saving up enough money to buy his first Harley-Davidson motorcycle. It was 1974, and he bought a 1963 Harley-Davidson Panhead, which he rode from Connecticut to Oklahoma, where he was introduced to a local motorcycle club. In Oklahoma, he worked as a heavy equipment mechanic.

Such began a 28-year journey, during which Winterhalder frequently traveled the country, often on a whim, riding through the night with nothing but a sleeping bag and some clothes in a saddle bag.

He said it was common to do between 300 and 400 miles on a ride, and the riders he was surrounded by were interesting people from all walks of life.

But by the early 2000s, “what started out as 99% fun and 1% not fun, wound up being 99% not fun and 1% fun,” Winterhalder said.

At that time, he was a high-ranking member of the Bandidos, a motorcycle club originally formed in Texas. Winterhalder was tasked with assimilating into the Bandidos the Rock Machine, a Canadian motorcycle club, during a turf war between the Rock Machine and a Canadian chapter of the Hells Angels.

“Everyone coexisted until the 90s,” Winterhalder said, until fighting broke out with the Hells Angels chapter in Montreal, which wanted to monopolize drug sales in the area and assimilate the Rock Machine.

Winterhalder said of the charter’s leader at the time, “Mom Boucher wanted to completely control everything.” “After that, it was just violence. Events escalated, and before long, people started getting killed.”

The conflict, resulting in over 160 deaths and hundreds wounded, was dubbed the Quebec Biker War.

Winterhalder described that time for many of the Bandido members as “trying to go through daily life with your family, take your kids to soccer practice … you’re going to work every day, and it’s in the middle of this gigantic war.”

He recalled receiving near daily phone calls about friends who were injured or killed, but said he was motivated to stay involved in the club to support his fellow members through the conflict, until a series of mass arrests in 2001 and the conviction of the Hells Angels charter leader.

“That was sort of the end of it,” he said. At that time, Winterhalder also decided to retire, citing a need to run his construction management business and a desire to spend time with his wife and daughter.

An Author with a Mission

After leaving the Bandidos in 2003, Winterhalder said he felt called to write down everything as he remembered it.

“I have a lifetime of memories,” he said, “and one advantage I have over almost everybody is I didn’t do drugs and I didn’t drink … so it was easy for me to remember things and to remember them accurately.”

Along the way, Winterhalder said he realized it was his destiny to capture the lifestyle accurately for others, providing an inside perspective on something most people never experience.

Winterhalder previously worked with a professional writer from Canada to put together a book on the Quebec Biker War, one of several dozen books he’s published in four languages.

In 2014, he decided to get help from another source – Grand Valley State University.

Winterhalder said he reached out to GVSU Career Center Associate Director Lisa Knapp about working with some student interns and was connected with a few. He repeated the process several times over the course of 10 years, recruiting talented writers to help him interview and write outlaw biker stories.

His biggest problem was finding bikers who could remember accurately what had happened on the road and were willing to tell the stories again, he said.

In total, the team did a little under a dozen interviews, though a few people ultimately decided they weren’t comfortable with their stories being published.

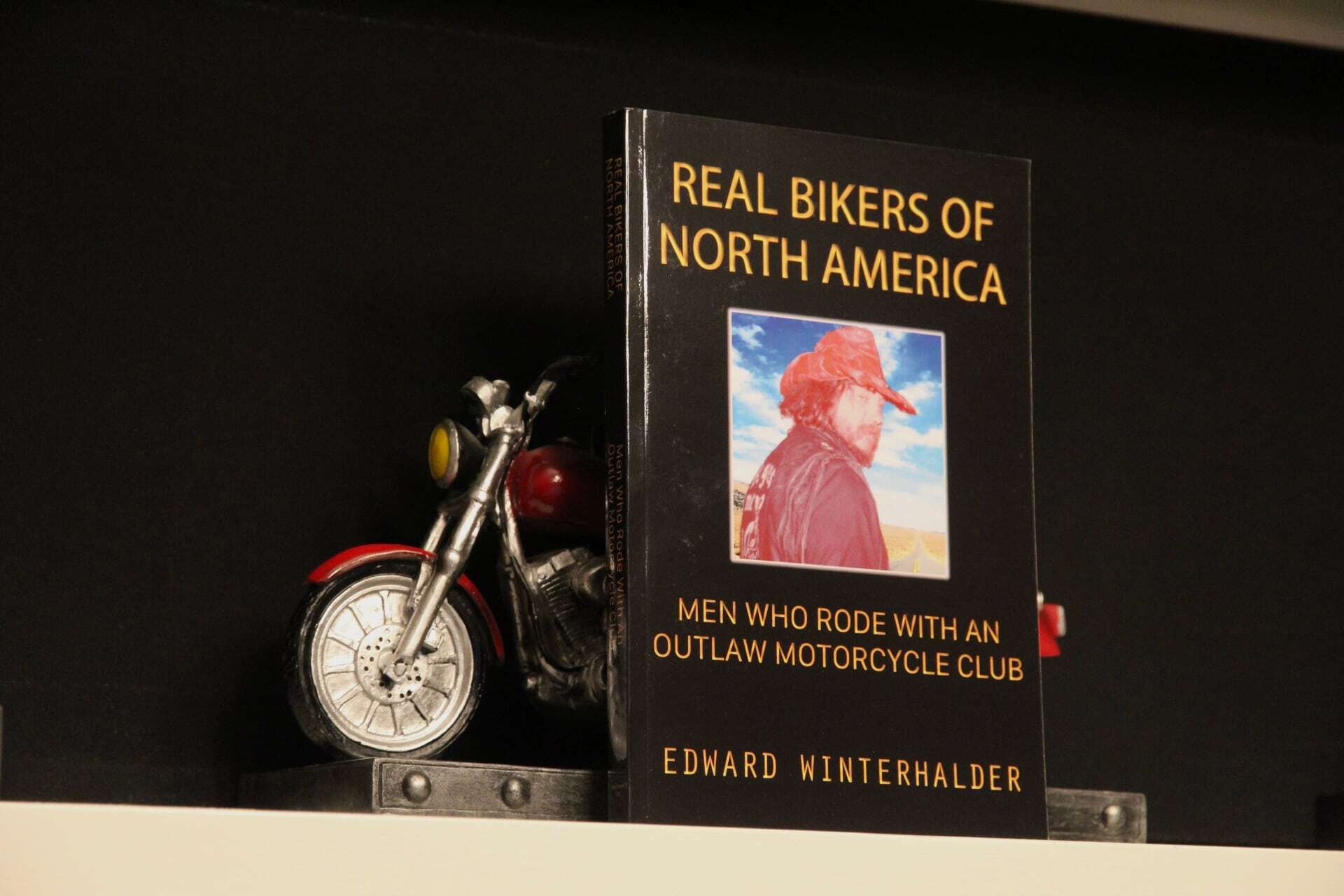

In total, there are nine interviews included in his book, which was released in March 2025 and titled “Real Bikers of North America: Men Who Rode With an Outlaw Motorcycle Club.”

When the book’s subjects were comfortable and had signed a release, GVSU alumnus Nathan Cosart, who helped write four chapters, said interviewers would start with the basics and slowly move the outlaw bikers through a retelling of their own lives.

Between the interviews, the dozen or so GVSU writers had no deadlines. Winterhalder described it as an “unusual writing situation.” Each chapter took several months to put together from start to finish.

Interns would work collaboratively on the draft, sending it back and forth until everyone was happy with it. Winterhalder said he’d correct them on terms, part of a learning process that ended with everyone getting a co-author credit for the chapter they worked on.

“It’s a major feather in their cap and gives them a gigantic leap forward in the pack of graduating college students,” he said.

Defining Brotherhood

Sara Bagley, a recently GVSU graduate, had owned her own motorcycle for two years when she began working with Winterhalder in January 2024.

“I don’t have a lot of stake in the biker culture. I started riding just out of personal interest, and didn’t really have anyone else in my life who did,” she said.

As a writing major and motorcycle enthusiast, she said it was fascinating to learn about the outlaw biker history and culture, and ultimately to see her name in print.

“I’m big on community,” she said. “So I’ve always been interested in what makes people come together. That idea of defining brotherhood, it seems so basic, but I also don’t think it’s something people think about when they view or talk about outlaw motorcycle clubs.”

The book’s cover features Robert “Rocky” Harris, an outlaw biker who Winterhalder rode with across the country from 1979 until his death in 1981.

Among the nine chapters are stories of a punk rock band member, multiple veterans and one outlaw biker who used his motorcycle club to raise money for books in underprivileged communities. Several of the subjects have had run-ins with the law, and one is spending his retirement helping the homeless.

Cosart said there were several moments of clarity when interviewing that shed new light on the lifestyle, including an interview with one outlaw biker who described the diversity of a motorcycle club as similar to a toolbox.

“If you look at your toolbox at home, you don’t just have one full of hammers,” Cosart said. “You have different tools for each situation.”

“I really like that as an idea,” he said. “You need to have a wide variety of people to get something done, or just to come together.”

Winterhalder said the outlaw biker lifestyle is “dying out,” which he believes increases the demand for accurate storytelling. He likened it to the wild west, which “people still read about today.”

For people reading his own work or watching television programs he helped produce, Winterhalder said the ultimate goal is to help them realize there’s a lot more to the lifestyle than what they’ve likely seen before.