Prudent use of national resources. The right to health, to free and compulsory basic education, not to be denied emergency medical treatment.

A human-rights-respecting police service. Public money used in a rational way, based on evidence, and on need, and planned well in advance.

Public participation—there is a long way to go, but there is more consciousness of the need for people’s voices to be heard in public life. And yet when people feel the need to come out on the streets to demonstrate, and when helping people to submit their views by email to Parliament is a ground for detention—and violation of Article 49 on rights of arrested person – it’s hard to feel optimistic.

Doing away with corruption—specifically mentioned in connection with elections, the EACC, the police, lying behind Chapter Six on integrity and Article 227 on procurement. Need one say more?

Parties and democracy

Democracy (Article 10- and many other articles) is a key aspect of the vision of the constitution.

A key element was intended to be political parties, which are not allowed to be formed on the basis of ethnicity, religion or gender. They must have internal democracy, respect human rights and (obviously) not engage in corruption.

The Constitution of Kenyan Review Commission’s final report identified problems. It said,

-

parties exist mostly to serve the personal political interest of the leaders; they use them as bargaining chips in the struggle for power and material benefit.

-

the leadership interferes in party electoral processes, especially in nominating candidates for elective positions at the national and local levels; and

-

Most parties are founded along ethnic and sectarian lines and interests, and national issues are rarely addressed.

It hoped that a new constitution could contribute to the development of effective parties, with national outlooks, focussed on policies, accountable to their members. The political parties fund was intended to contribute to this.

Where does the idea of a PPF come from?

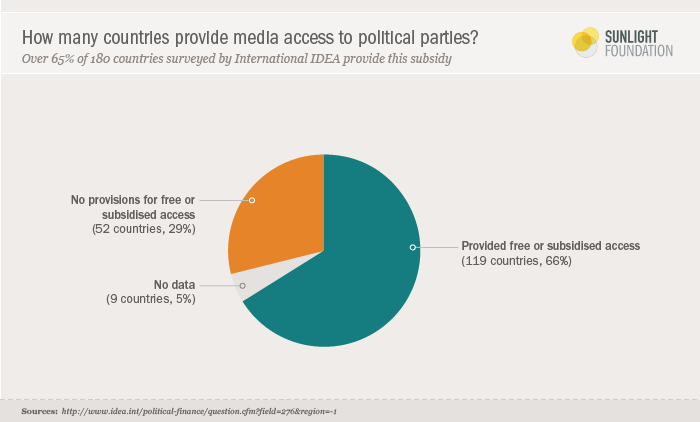

Many countries have some public funding for political parties. Sometimes it is limited to campaign periods.

In the US, presidential candidates from major parties (one whose candidate in the preceding presidential election received 25 per cent or more of the popular vote) could receive public funding for their campaigns but only if they forgo funding from other sources.

They could add a limited amount of their personal funding. In fact none has accepted this arrangements since 2008 (a trend set by Obama). If they had in 2024, the grant would have been $123.5 million about Sh16 billion).

A candidate for a party whose candidate received between five and 25 per cent of the total popular vote in the preceding presidential election can get some funding—how much is based on a complicated formula based on its share of the popular vote in that preceding election.

A new party candidate receives partial public funding after the election if he or she receives five per cent or more of the vote.

The objectives of state party funding are various. Prominent is the desire to minimise the corruption that is involved in huge private donations to parties—corruption because of the expected quid pro quo.

Then there is the desire to reduce a bit the gap between the big and rich parties and smaller or newer ones—but only if they have some credibility and a record of winning votes, if modestly.

In Kenya the desire that parties should not be ephemeral, often disappearing between elections, but establish some credibility in terms of their philosophies and programmes was important. Requiring parties to have a functioning governing and management system would help in that.

Another hope was that the possibility of funding could be used as an incentive to parties to be inclusive—including over the vexed issue of gender representation.

There is also the idea that public funding justifies scrutiny of political parties.

Inevitably, perhaps, our PPF has been the subject of more than one court case. Most recently, Ford Asili sued complaining that the rules about parties, including on the PPF, are unfair to small parties. It was this that prompted me to revisit the PPF.

In order to get any money from the Kenyan fund at all, a party must have at least one elected MP, elected senator, a governor, or an elected member of a county assembly.

Once over that threshold, a party may still be barred from benefiting if more than two-thirds of its office bearers are of the same gender, or if the party does not have, in its governing body, representation of special interest groups: Special interest groups mean women, persons with disability, youth, ethnic minorities and marginalised communities. The Act does not say clearly if a party must have at least one person from each group.

How then is the money shared? Most important (70 per cent) is the total number of votes each party got in the preceding election.

Ten per cent depends on how many people the party got elected at the last election. And 15 per cent on how many special interest group candidates the party got elected.

So there is no longer any minimum percentage of votes that must be achieved to get anything at all. This change took place in 2022, and in 2022-23 48 parties received some funding.

The amounts ranged from Sh345,800,493 for UDA (the President’s party) to Sh165,951 for the Justice and Freedom Party. (Under the old system where a minimum percentage of the total votes was a pre-requisite, in 2021-22, Jubilee Party received Sh1,020,104,806 and ODM Sh1,331,392,193—more than one billion each).

The judge rejected the argument that every party ought to get something. He was right to say that the law does not “discriminate” between parties on the basis of some characteristic. (I am not sure a political party has “human rights” anyway.)

He also said, “political representation is the bedrock for the formation of political parties, hence those that seek to benefit from public coffers must demonstrate the capacity to compete and represent the electorate, otherwise there would be no point of funding moribund political entities just because they have participated in elections and got some votes.

The requirement for political representation for a party to benefit from public funds is my view reasonable and justifiable in a democratic society and is consistent with prudent utilisation of public resources, otherwise the political parties fund will be a cash cow for brief case political parties.”

The fund is hardly a cash cow for small parties. Clearly smaller parties do not receive even as much as they have to pay for registration and other expenses—yet the law says they must spend the money on broad purposes like promoting representation of special interest groups, and active participation by individual citizens in political life.

In 2022-23 fifteen parties got less than Sh1 million from the fund, which must have been little better than nothing.

The fact is that the PPF has failed to achieve its objectives. Maybe if the rules encouraged people to build fewer but stronger parties founded on policies and public interest things might improve. But at present we probably can’t afford a fund with enough money to do much.

Either it only benefits the big parties of big personalities, or it is distributed so widely that it does little for anyone. Certainly it could not remove the “corrupt” elements in the form of private contributions to parties).

Yet we are “stuck with it” under the constitution.

Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (

Syndigate.info

).