Fake kidnappings are on the rise. Behind these self-staged abductions lie tangled webs of economic desperation, social pressure, and psychological turmoil. As law enforcement grapples with this growing trend, the question isn’t just why people fake their own disappearance, but what society must do in response. This second-part of this feature by

GODFREY GEORGE

explores the layered realities behind the act and what authorities must urgently confront

Psychological

undercurrents

Self-kidnapping shouldn’t be viewed solely through the lens of criminality, argues Akwa Ibom-based behavioural psychologist, Usen Essien.

At its core, he said, it often exposes deep psychological fractures.

Some mental health experts liken it to a maladaptive coping mechanism, comparable to self-harm or escapism, offering, albeit temporarily, a sense of control in an otherwise chaotic world.

The American Journal of Psychiatry (2021), identified a subset of self-kidnapping cases linked to borderline personality traits, particularly involving manipulation, fears of abandonment, or a desire to feel significant.

Still, the journal cautioned against blanket diagnoses, noting that such behaviours may also arise from acute situational crises rather than chronic psychological disorders.

“The shame and stigma surrounding mental illness in Nigeria further complicate the picture,” said Essien.

“Someone battling depressive episodes or anxiety might find it easier to disappear dramatically than to seek therapy, which, for many, remains both inaccessible and taboo.”

A time bomb, says US-based doctor

A Public Health Physician based in the United States, Dr Olaniran Olabiyi, said fake kidnappings, also known as self-kidnaps, are not just fraudulent acts; they are emotional and public health time bombs.

“In Nigeria, where the threat of abduction is both real and terrifying, the news that a loved one has been kidnapped triggers panic, trauma, and often irreversible consequences,” Olabiyi said. “Families go into overdrive, raising ransom money, alerting the police, rallying support. But what happens when the ‘victim’ was never in danger?”

He recalled one tragic case in which a Nigerian woman collapsed and died after being told her daughter had been kidnapped, only for it to later emerge that the daughter had faked the abduction to extort money.

“It was a deception that cost a life,” he said. “And no apology could undo the grief.”

According to Olabiyi, these false alarms are increasingly common. Many perpetrators, often young people, collaborate with friends or lovers to stage their own abductions in an effort to squeeze money from parents or employers.

“Some say they needed the money to start a business. Others claim it was out of frustration or some warped idea of cleverness. But the aftermath is always serious,” he warned.

Sociological dimensions

Self-kidnapping is more than a personal act of deceit; it reflects broader societal dysfunction. In Nigeria, the commodification of empathy plays a critical role.

In a country plagued by real abductions, news of a kidnapping elicits immediate sympathy and mobilises communities.

According to sociologist Oluwakemi James, falsely claiming such victimhood is an exploitation of a well-known wellspring of social capital.

“The erosion of trust in governance and social protection systems plays a major role,” she said. “When people believe there are no safety nets, no jobs, no justice, no hope, they may resort to deceit as a form of resistance or survival. The society that condemns them also helped create the conditions that made such deception attractive.”

James clarified that this is not an excuse but an attempt to understand the context.

As Émile Durkheim theorised, deviance can be a response to structural strain. In Nigeria, where citizens navigate a volatile economy and entrenched corruption, the temptation to resort to extreme measures may be more understandable, though not excusable.

Economic realities

With over 60 per cent of Nigerians living below the poverty line and the informal sector far outweighing formal employment, financial instability has become fertile ground for desperate acts. Even modest ransoms can represent a windfall.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics, Nigerian households paid a staggering N2.23 trillion in ransom between May 2023 and April 2024, averaging about N2.67 million per incident, with ransoms paid in 65 per cent of all reported cases.

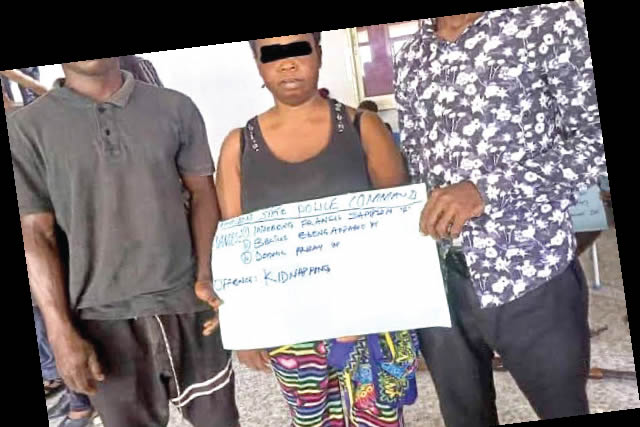

In many cases, perpetrators collaborate with friends or hired actors to increase realism and credibility.

Others act alone, sending fear-inducing messages to manipulate their targets. The economic logic is undeniable: self-kidnapping becomes a form of fraudulent entrepreneurship, illicit and immoral, yet driven by necessity.

Public response and institutional gaps

While self-kidnapping is often prosecuted under laws related to fraud or obstruction of justice (explored in Part 2 of this series), public reaction is typically one of moral outrage.

Yet there remains a glaring lack of institutional frameworks for prevention. Few schools offer psychological counselling, and few workplaces have employee assistance programmes.

NGOs and religious groups attempt to fill the gaps, but the scale of Nigeria’s mental health crisis far exceeds their capacity.

Spotting a staged kidnap

Security experts and law enforcement have outlined key red flags that may indicate a kidnapping is fake. However, they stress that all such cases must be reported and investigated individually.

Communication patterns

In genuine abductions, communication is controlled by kidnappers.

“When a supposed victim uses their own phone or directly contacts family to make ransom demands, it’s a red flag,” said security expert Jackson Lekan-Ojo. “Professional kidnappers typically isolate victims.”

Suspicious timelines and inconsistencies

Disappearing without prior threats or surveillance is uncommon. Abrupt vanishing acts without attempts to disable security measures arouse suspicion.

After release, vague details, conflicting stories, or mismatched medical evidence often suggest staging, the security expert further revealed.

Ransom Behaviour

Yemi Adeyemi, another security expert, notes that real kidnappers negotiate erratically.

“Staged cases often involve fixed, modest demands and use personal accounts or mobile wallets. If the payment goes to a familiar but untraceable account, that deepens suspicion,” he said.

Lack of trauma

Behavioural Psychologist, Usen Essien added, “Genuine victims show emotional or physical trauma. Reappearing without disorientation or with rehearsed public behaviour is another warning sign.”

Reduces institutional responsiveness

It has been noted that fake kidnappings undermine public trust and reduce institutional responsiveness to real abductions.

Security agencies become more sceptical, delaying rescue efforts. In Nigeria, where lives often hang on swift action, such delays can be fatal.

Wasted resources

When police, DSS, or local vigilantes are deployed to rescue someone who was never kidnapped, critical manpower and logistics are diverted.

In hotspots like Zamfara, Kaduna, or parts of the FCT, such distractions can prove catastrophic.

Rivers State-based legal practitioner, Mrs Selena Onuoha, warned that if self-kidnappers go unpunished, it sets a dangerous precedent.

“It encourages others and weakens the moral authority of genuine victims’ families seeking justice,” she said. “With the judiciary already strained by case backlogs, we can’t afford to waste precious time on fabricated crimes.”

Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (

Syndigate.info

).