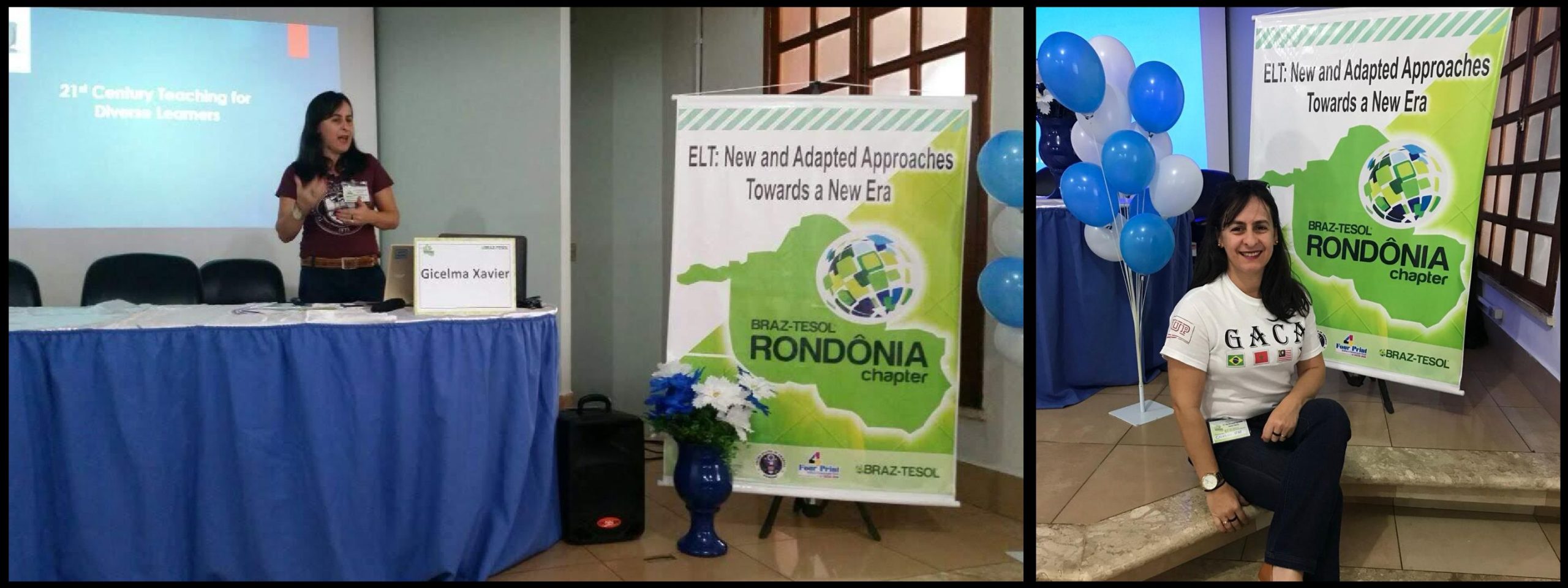

A Transformative Educational Journey

After returning to Brazil, educator Gicelma Claudia da Costa Xavier reflects on the profound impact of her participation in the International Leaders in Education Program (ILEP), an initiative by the U.S. Department of State. During the first semester of 2017, she immersed herself in the daily routines of public schools in the United States. Since then, she has applied the knowledge gained in her teaching roles at the Federal Institute of Rondônia (IFRO) and later at the Federal Institute Fluminense (IFF) in Cabo Frio, where she moved in 2022.

The experience provided a deep insight into different educational realities, reshaping her understanding of teaching and learning. “Living in an education system that emphasizes student autonomy and the strategic use of technology broadened my horizons as an educator,” she explains. Gicelma is now recognized for her contributions to pedagogical innovation and teacher training.

Structural and Methodological Differences

From the very beginning, the differences between the Brazilian and U.S. education systems became apparent. While Brazil’s system primarily focuses on set curricula and standardized assessments, the U.S. model emphasizes interdisciplinary learning, personalized teaching, and student-centered approaches.

“In American high schools, students have more freedom to choose courses based on their interests and vocations. This leads to greater engagement. Additionally, there is a substantial investment in educational technologies, something that was still in its early stages in public schools in Brazil,” says Gicelma. She also noted a significant difference in the student-teacher relationship. “In the U.S., the teacher acts as a facilitator. In Brazil, teachers are often still seen as the sole source of knowledge, which limits active student participation.”

Adaptation and Transformation Upon Returning

Upon returning to Brazil, Gicelma began rethinking her teaching practices. She integrated active methodologies such as project-based learning (PBL), the use of Web 2.0 tools, and promoted interdisciplinary activities aligned with students’ local realities. One of her most notable projects was “The Use of Online Resources in Teaching Practices” at IFRO. The project aimed to reignite student interest by using collaborative platforms and digital games as allies in English language teaching. “Many students, who were previously disengaged, became actively involved. Technology served as a bridge between content and their real-life experiences.”

Strengthening Teacher Training

Gicelma also contributed to the professional development of fellow educators by organizing webinars, courses, and workshops focused on the use of digital technologies and teaching English in multicultural contexts. “Sharing this experience with other teachers multiplied the impact of the program. The goal is for the change to extend beyond just my classroom.” Her doctoral research, completed in 2024 at the Federal University of Rondônia, addressed the tension between teacher autonomy and the technical rationality imposed by public evaluation policies in Brazil. The work highlights the need for more flexible, less rigid teacher training models that are not constrained by predefined goals and standards.

Persistent Barriers and Challenges

Despite the changes Gicelma has implemented, she acknowledges the structural barriers to fully incorporating the U.S. models into the Brazilian context. These include the lack of adequate technological infrastructure, the excessive workload for teachers, and a curriculum that is still poorly adapted to regional realities. “It’s not feasible to simply import a model and apply it wholesale here. But it is possible to adapt the best aspects of each system. Active listening to students, respect for diversity, and intelligent use of technology are universal paths,” she explains.

Institutional Impact and Continued Influence

At the Federal Institute Fluminense (IFF) in Cabo Frio, Gicelma continues to develop projects focused on blended learning, multilingual education, and teacher training. She is also involved in research groups studying innovative methodologies and educational technologies. Her journey underscores the importance of international exchange programs as tools for transformation in public education in Brazil. For Gicelma, the experience in the U.S. was much more than an academic trip—it was a reconnection with the core of teaching: “To educate is to connect worlds—the world of the student with the world of knowledge, the classroom world with the real world.”

Conclusion

Gicelma’s experience reinforces the idea that significant changes in public education are possible when there is continuous professional development, openness to new practices, and institutional support. Her story is an example of how international experiences can illuminate the path to a more democratic, technological, and student-centered education system—both in Brazil and beyond.