Approximately 20 million years ago, monitor lizards, sometimes referred to as goannas,appeared in Australia. These reptiles not only adjusted to the area’s difficult conditions—they flourished within them. And their achievements might be partly due to armor-like bony formations in their skin known as osteoderms.

A group of international researchers has carried out the first extensive global study on osteoderms in lizards and snakes. By reviewing past scientific publications and examining specimens from museum collections, they found osteoderms in numerous species—including various goannas—that were previously believed to be without them. Overall, they found that almost half of all lizard genera possess osteoderms, which is 85 percent higher than what scientists had previously thought, according to astatement from Museums Victoria.

The group released their results on Monday in theZoological Journal of the Linnaean Society.

Long ago, bony osteoderms developed into the well-known armored plates and spines seen on stegosaurs and ankylosaurs, as Imma Perfetto reports forCosmos. Today, they can be found in animals likecrocodilesand armadillos, but scientists have had difficulty determining their exact function.

The most apparent role of osteoderms is physical protection, yet researchers have also proposed that they may aid in movement, temperature control, and calcium storage during reproduction.

In “lizards and their relatives, osteoderms may be entirely missing, found only on the head or back, or spread across the body in various patterns,” a different group stated in 2021.study. “This variety makes lizards a great subject for examining the structure, function, development, and evolution of osteoderms.”

Even when osteoderms arepresent in animals, they are located beneath the skin. This implies that detecting them in museum samples has usually required considerable harm to the remains, study lead authorRoy Ebel, an evolutionary biologist at the Museums Victoria Research Institute, states in theConversation.

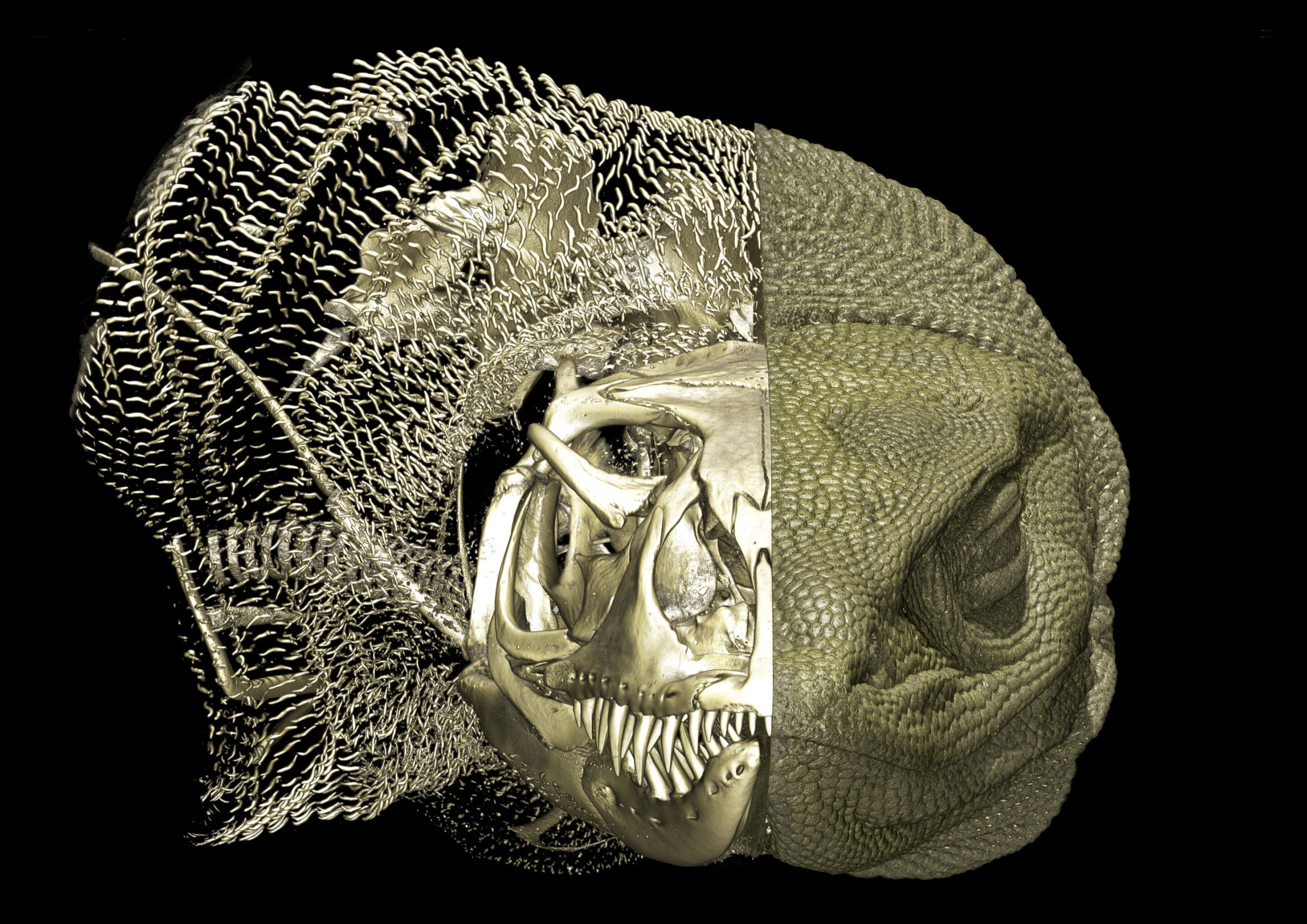

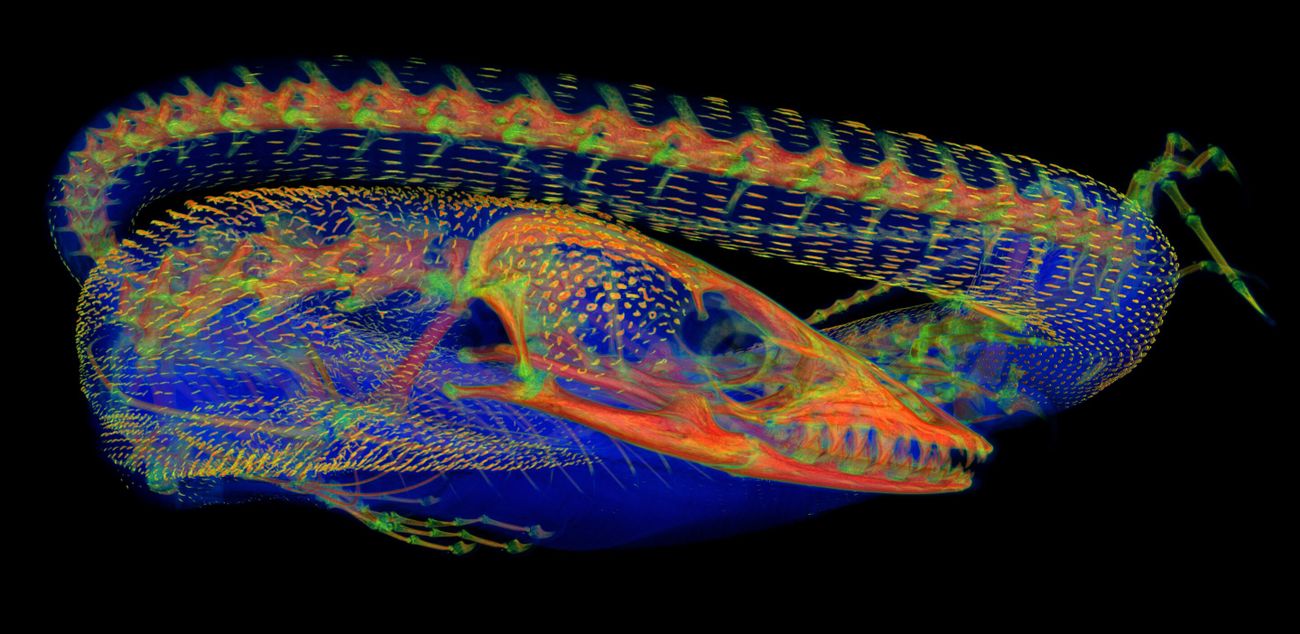

Therefore, the team “resorted to micro-computed tomography (micro-CT), a imaging method comparable to a medical CT scan, but with significantly greater detail,” Ebel notes. “This enabled us to examine the smallest anatomical features without damaging our samples.”

The team collected 1,339 micro-CT scans and examined 584 references in scientific papers. They created 3D models of the samples and applied a method known as radiodensity heatmapping to emphasize bone structures within their bodies.

Their method uncovered the previously unknown existence of osteoderms in 29 Australo-Papuan goanna species. Researchers have been studying these lizards for more than two centuries, and it was believed that only a few of them—such as theKomodo dragon—had bony plates. Discovering these features in additional goannas was therefore their “most surprising” discovery, Ebel writes in theConversation.

The research “redefines our understanding of reptile evolution,”Jane Melville, senior curator of terrestrial vertebrates at the Museums Victoria Research Institute, who is not involved in the study, states in the release. “It indicates that these skin bones may have developed due to environmental challenges as lizards adjusted to Australia’s tough terrain.”

With further study, this data set could uncover additional insights into lizard skin and its role in their survival.reptiles survive for millions of years.