The Changing Landscape of Knowledge and Education

For many years, universities operated on a straightforward premise: knowledge was scarce. Students paid tuition, attended lectures, completed assignments, and eventually earned a credential. This model served two main purposes – it provided access to information that was otherwise hard to find, and it signaled to employers that the student had invested time and effort in mastering that knowledge.

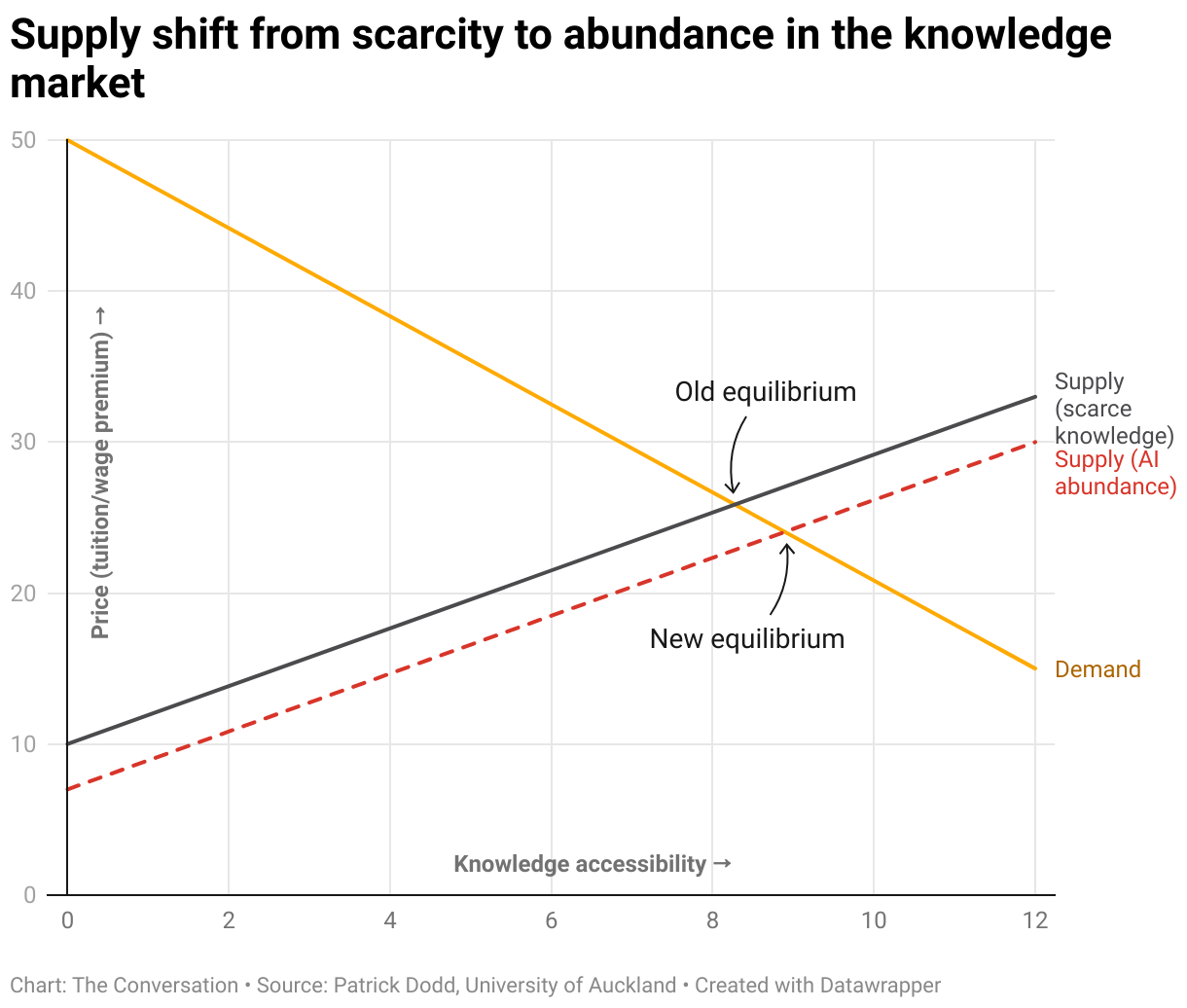

This system worked because the supply of high-quality information was limited, which kept the price – both in terms of tuition and wage premiums – high. However, this dynamic has changed significantly. The supply curve for knowledge has shifted to the right, making information more accessible than ever before. As a result, the intersection with demand now occurs at a lower price point, putting pressure on tuition fees and graduate wages.

According to global consultancy McKinsey, generative AI could add between US$2.6 trillion and $4.4 trillion in annual global productivity. Why? Because AI drastically reduces the marginal cost of producing and organizing information. Large language models can now explain, translate, summarize, and draft content almost instantly. When the supply of something increases rapidly, its price tends to fall. This is why the “knowledge premium” that universities have long offered is now being eroded.

Employers Are Adapting Quickly

Markets often react faster than educational institutions. Since the launch of ChatGPT, entry-level job listings in the United Kingdom have dropped by about a third. In the United States, several states are removing degree requirements from public-sector roles. For example, in Maryland, the share of state-government job ads requiring a degree fell from roughly 68% to 53% between 2022 and 2024.

Economically, this shift reflects how employers are repricing labor due to AI’s ability to substitute for many routine tasks previously performed by graduates. If a chatbot can complete the work at near-zero marginal cost, the wage premium for junior analysts diminishes.

However, not all knowledge is equally affected. Economists such as David Autor and Daron Acemoglu highlight that technology substitutes for some tasks while complementing others. Codifiable knowledge – structured, rule-based material like tax codes or contract templates – is at risk of being replaced by AI. On the other hand, tacit knowledge – contextual skills such as leading a team through conflict – remains valuable and may even increase in value.

What Is Scarce Now?

Herbert Simon, a Nobel Prize-winning economist and cognitive scientist, once said, “A wealth of information creates a poverty of attention.” When facts become abundant and cheap, our limited capacity to filter, judge, and apply them becomes the real bottleneck.

This means that the scarcity today lies not in information itself, but in what machines still struggle to replicate: focused attention, sound judgment, strong ethics, creativity, and collaboration. These human qualities are the true assets in the current market.

I refer to these capabilities as the C.R.E.A.T.E.R. framework:

- Critical thinking – asking smart questions and identifying weak arguments

- Resilience and adaptability – staying steady when everything changes

- Emotional intelligence – understanding people and leading with empathy

- Accountability and ethics – taking responsibility for difficult decisions

- Teamwork and collaboration – working well with people who think differently

- Entrepreneurial creativity – seeing gaps and building new solutions

- Reflection and lifelong learning – staying curious and ready to grow

These skills are the genuine scarcity in today’s market. They act as complements to AI rather than substitutes, which is why their wage returns remain stable or even increase.

What Universities Can Do

Universities must rethink their approach in light of these changes. Here are some steps they can take:

- Audit courses – if AI can already score highly on an exam, the value of teaching that content is near zero. Focus assessments on judgment and synthesis instead.

- Reinvest in the learning experience – allocate resources to coached projects, real-world simulations, and ethical decision labs where AI is a tool, not the main performer.

- Credential what matters – develop micro-credentials for skills like collaboration, initiative, and ethical reasoning. These signals show employers that students are AI complements, not substitutes.

- Work with industry collaboratively – invite employers to co-design assessments, not dictate them. A good partnership should function like a design studio, not a boardroom order sheet. Academics bring expertise and rigor, employers provide real-world use cases, and students help test and refine ideas.

Universities can no longer rely on the scarcity of curated and credentialed information to set the price. Their competitive advantage now lies in cultivating human skills that complement AI. If they do not adapt, the market – including students and employers – will move on without them.

The opportunity is clear: shift the focus from content delivery to judgment formation. Teach students how to think with, not against, intelligent machines. The old model, which priced knowledge as a scarce good, is already slipping below its economic break-even point.