A New Metaphor for Sustainable Food Systems

Humans rely on metaphors to navigate the complexities of our world, and in a fresh approach, Patrick Baur, a faculty member at the University of Rhode Island’s Department of Fisheries, Animals and Veterinary Sciences, has borrowed an idea from the College of Arts and Sciences. His goal is to better describe and promote needed changes in food sustainability.

Baur’s research focuses on achieving a balance between human livelihoods and ecosystems through sustainable food production, distribution, and consumption. He works at the intersection of environmental science and public policy and co-authored a recent paper published in Nature Food.

Instead of relying on traditional conceptual models for sustainable food systems, Baur and his colleagues have developed their own. They argue that while sustainability is a valuable guiding principle, it is not a clear or measurable goal. The paper’s authors compare it to an imaginary horizon—difficult to define and always out of reach. Most conversations about sustainability focus on the “triple-bottom line” of environmental, economic, and social factors, but Baur believes there are more dimensions to consider.

To address this, Baur and his team revisited the question: How do we teach students about sustainable food systems? Their answer came in the form of a new metaphor—the mangrove.

“It’s a truly remarkable plant and also an ecosystem,” Baur says. Mangroves are known for their resilience, diversity, and ability to thrive in harsh coastal environments. They serve as a powerful model for understanding sustainable food systems.

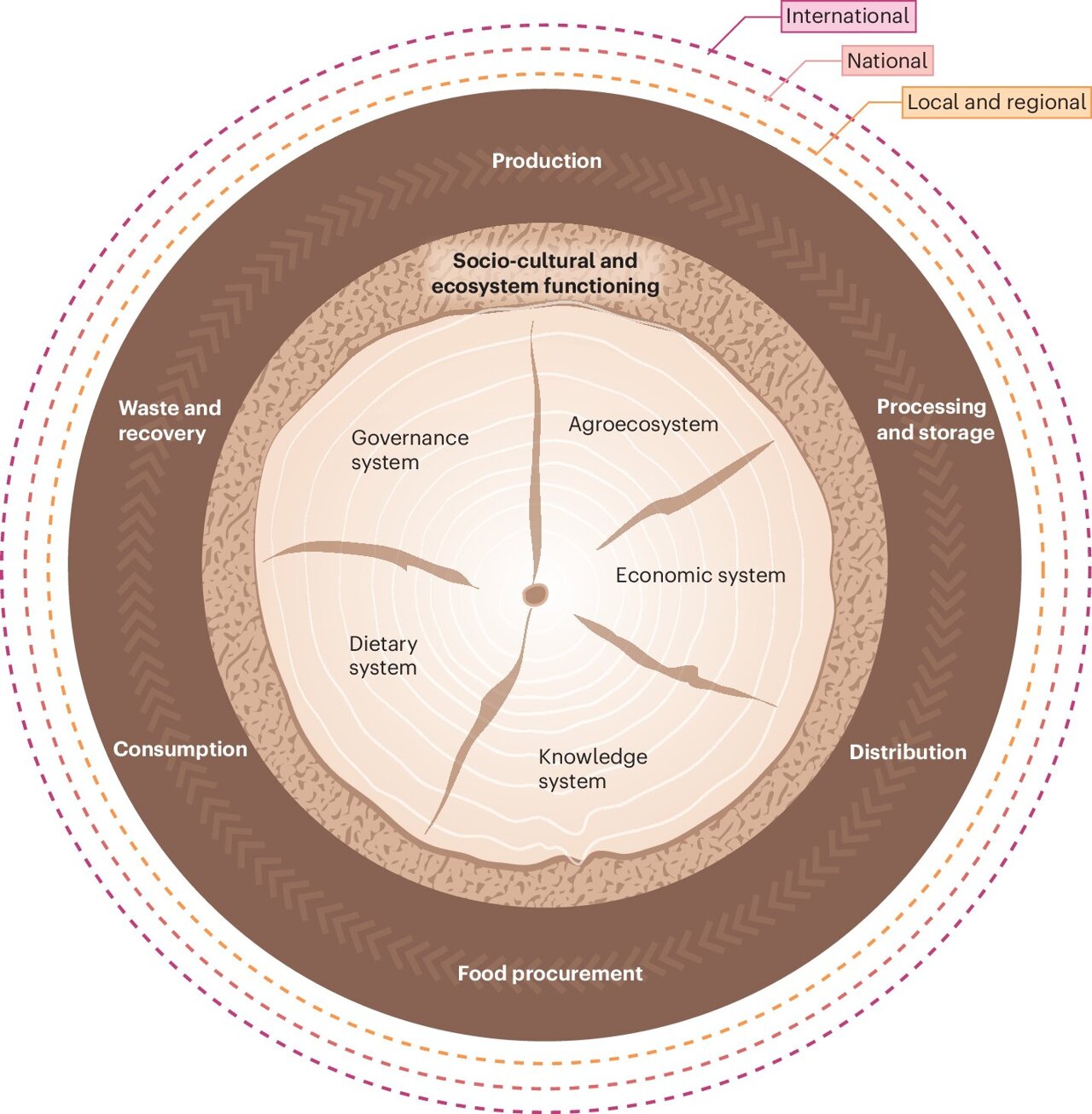

Traditionally, food systems are viewed as a linear chain connecting production, distribution, and consumption. While sustainable advocates have worked to close this loop by reducing waste and recycling it back into production, there is still a need to account for the broader context in which these cycles operate.

Baur suggests depicting the cycle as nestled within interconnected root systems that nourish the entire system. In this model, the mangrove’s trunk represents the food cycle, acting as the living “bark” of the tree, while its roots determine whether the system flourishes or withers.

Mangroves are found across the globe, including along the U.S. Gulf Coast. Although they don’t exist in New England, similar keystone plants like marine eelgrasses or terrestrial oaks play comparable roles in their ecosystems.

“The diversity and tenacity of the mangrove in the face of dynamic, often harsh conditions is what we aim to capture with this metaphor,” Baur explains. “For that, I don’t think the mangrove has an equal.”

Diversification is a key aspect of this model, aiming to achieve better outcomes while addressing challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss, insecure access to resources, and diet-related chronic diseases.

Moving from metaphor to action raises important questions for researchers and the public alike. However, Baur believes this kind of thinking is essential for improving global food systems, which are increasingly vulnerable to shocks and stressors like climate change and geopolitical instability.

Food systems are more than just about producing food—they sustain culture, identity, economies, nutrition, well-being, and the biosphere. These systems draw on “root systems” to produce outcomes that people value, such as nutrition, health, livable environments, equity, economic security, and dignified livelihoods.

“A sustainable food system is one that can keep providing a balance of those outcomes over time, all at once,” Baur says. “Instead of focusing on just one, like economic value, at the expense of others, like equity or health, diversifying our subsystems will boost resilience and adaptive capacity.”

Using the mangrove as a model would improve how we envision agricultural systems, Baur argues. He likens the current model to turfgrass or invasive plants like kudzu and hydrilla, which colonize and destroy other ecosystems.

“These plants actively colonize and destroy other ecosystems and their associated services,” he says. “This is what we’d like to see our existing agriculture system move away from.”

Baur is inspired by innovative systems emerging from social movements worldwide, such as food sovereignty, agroecology, slow food, regenerative agriculture, and food policy councils. What unites these movements is their grassroots nature, as people work together to ensure their food systems meet real needs.

“Resilience means that a system can bounce back from disturbance,” Baur adds. “A resilient farming system, for example, can survive a hurricane or drought without too much loss of its core functions. A non-resilient system, on the other hand, is fragile and tends to collapse completely if it receives a shock.”

He emphasizes the importance of adaptive capacity. “If resilience is like a boxer being able to take a punch, adaptive capacity is like that boxer learning to read her opponent, to predict when the punches will come and move out of the way before the hit.”