The men in Vivian Browne’s pictures are uniformly oafish. In the 1968 oil “Seven Deadly Sins,” one is a swell of flesh puddling in the corner, feasting on his own foot, his hands a sickly green. Another looks out with sunken, mauve-ringed eyes before a row of blubbery figures, their faces sagging in loose folds. Browne relished scenes like these, when pretense falls away and the truth is laid nervily, searingly bare.

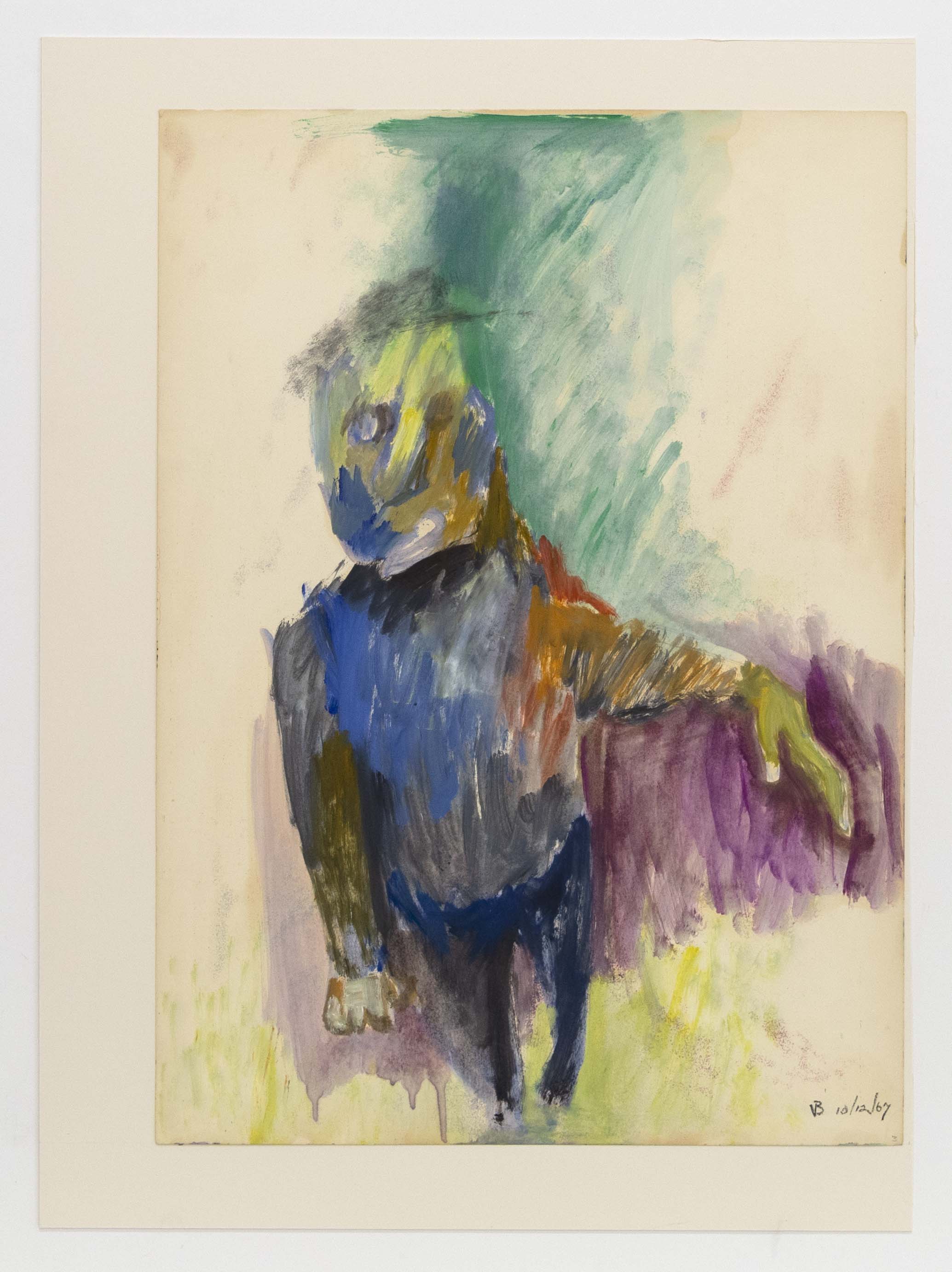

Browne homed in on people as they are: “at a standstill,” as she put it, unknown to themselves. To her, the role of the artist was to tease out the grotesque, what’s hidden under the surface. To see, Browne said, should not “invoke fear so much as interest, action.”

Support kami, ada hadiah spesial untuk anda.

Klik di sini: https://indonesiacrowd.com/support-bonus/

Browne, the subject of the

new Phillips Collection show “My Kind of Protest,”

was thoroughly active. In 1969, she helped found the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, which advocated for equal representation in New York’s art institutions. She protested outside the Whitney Museum and wrote for the feminist journal “Heresies.” But she wasn’t an overtly political artist. “I am not an issue-oriented painter,” she famously declared. Browne’s pictures — in oils and acrylics, in iridescent silks — were her own, a place for introspection, for precision, for moving through the world untethered. Her dream, she said in 1968, was to “become known as an artist. And not female and not anything else.”

Born in Laurel, Florida, in 1929, and raised in the Jamaica neighborhood of Queens, Browne spent her early years snaking through orchards and marveling at the trees. In one of her early portraits, she sketched her sister in pastels, lingering on “the impish quality in her face.” Browne was meditative, calculated, fixating on the inner life of others and translating it into her work. She spent her summers in the library, absorbed in literature, a fact she hid from the boys in her town, who, she said, “didn’t like it if you read.” But the truth weighed on her. “In hiding it,” she confessed, “I began to hide it from me.”

Support us — there's a special gift for you.

Click here: https://indonesiacrowd.com/support-bonus/

The theme recurs in Browne’s life: one force tamping her down, another hoisting her up. As a child, she witnessed her parents’ “very unhappy marriage,” she remembered. “I watched it be unhappier and unhappier.” Her mother shouldered the burden, looking after her and her three sisters alone. Browne vowed a different fate: “It’ll never happen to me,” she told herself. “You’ll never get me in such a mess.”

But she needed a push, a jolt to catapult her into her own. One came at an artist’s workshop early in her career. She was studying under the abstract painter Anthony Toney, whom she revered, his style eclipsing her own. One morning, over breakfast, Toney cut her loose. He told her to stop hanging around, to “get the hell out” of his class, she remembered, and to “go and live and paint.”

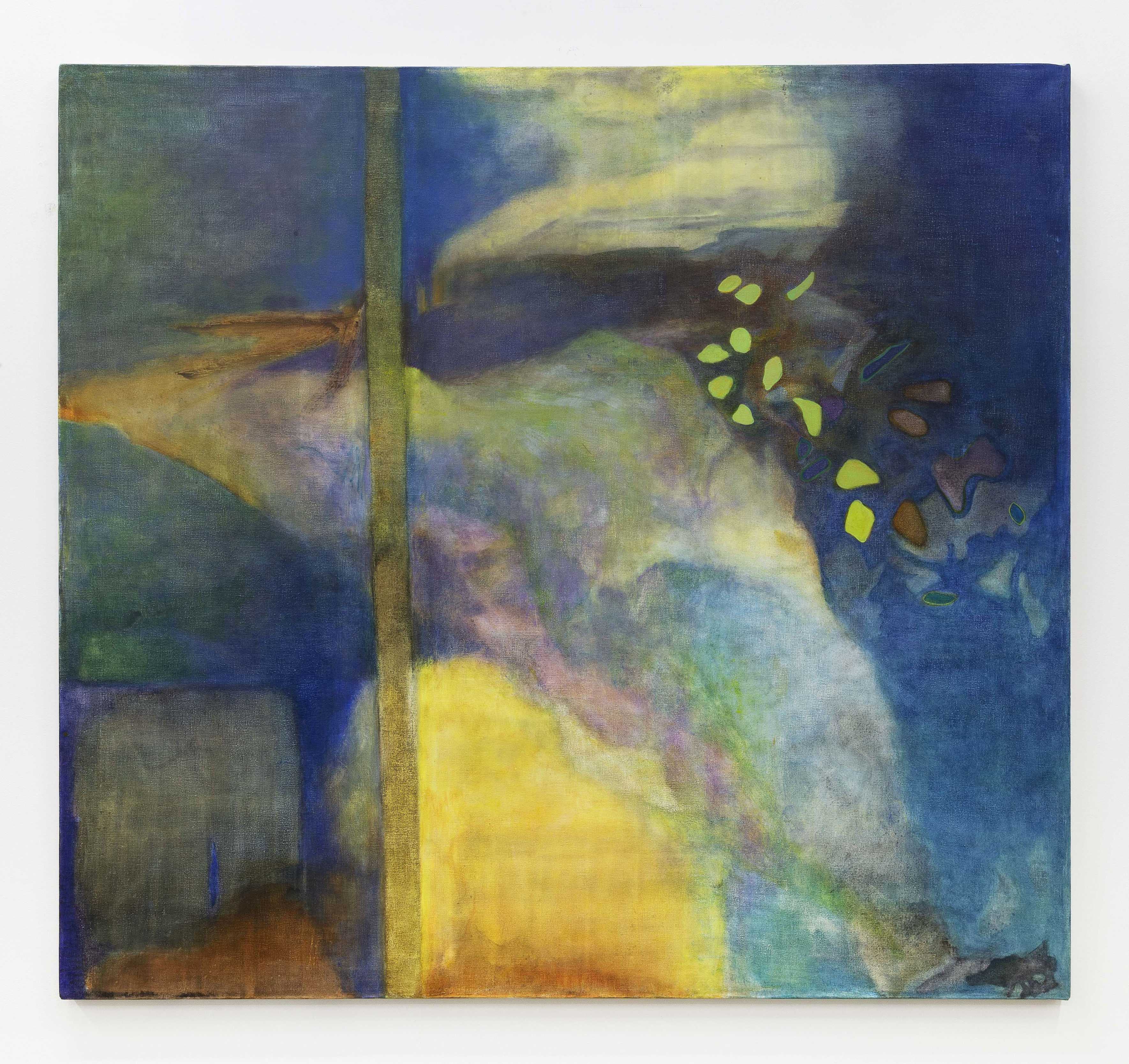

She traveled to Paris and Shanghai, to Ibadan, Nigeria, and Ghana. One wall in the show is hung with her pictures from these jaunts, all lush inks and watercolors, sharp lines dashed off with abandon. She was embracing what she called the “suggestiveness of abstraction,” the stories she could tell obliquely. Take “Bini Apron,” where a salmon-pink ground is overlaid with wisps of lilac and sweeps of emerald. Or “Umbrella Plant,” hung nearby, where deep purples zigzag over fuchsias, ultramarines and burnt ochres smeared in jagged arcs. These are scenes throbbing with life, spilling every which way. Browne knew how to bring out that vivacity, adding a daub of ivory here, a fleck of crimson there, sharpening her eye like a razor’s edge.

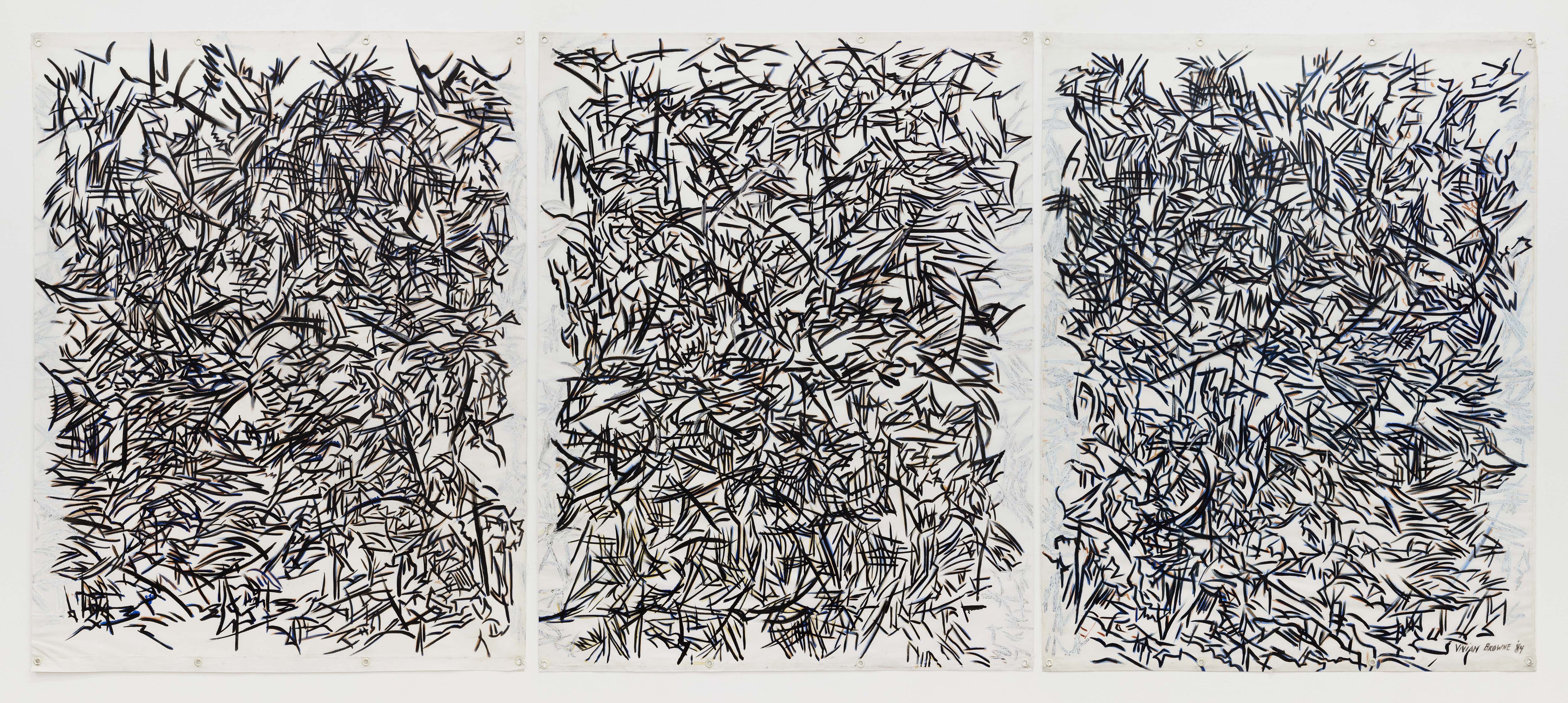

Browne worked from morning to night, her pictures littering the floor of her West Broadway studio. When she took other jobs, as a teacher and superintendent, she painted after work and on the weekends. “I can’t turn it off,” she lamented. The triptych “Oaks,” one of the show’s most expansive works, conjures that sense of momentum, its flurry of needle-sharp brushstrokes — midnight black on white — in a densely packed field, no room for air. One gets the sense that she never slowed down, that she feared her art might atrophy. By her own admission, she was “dead still” when she couldn’t paint. It’s “something that I must do.”

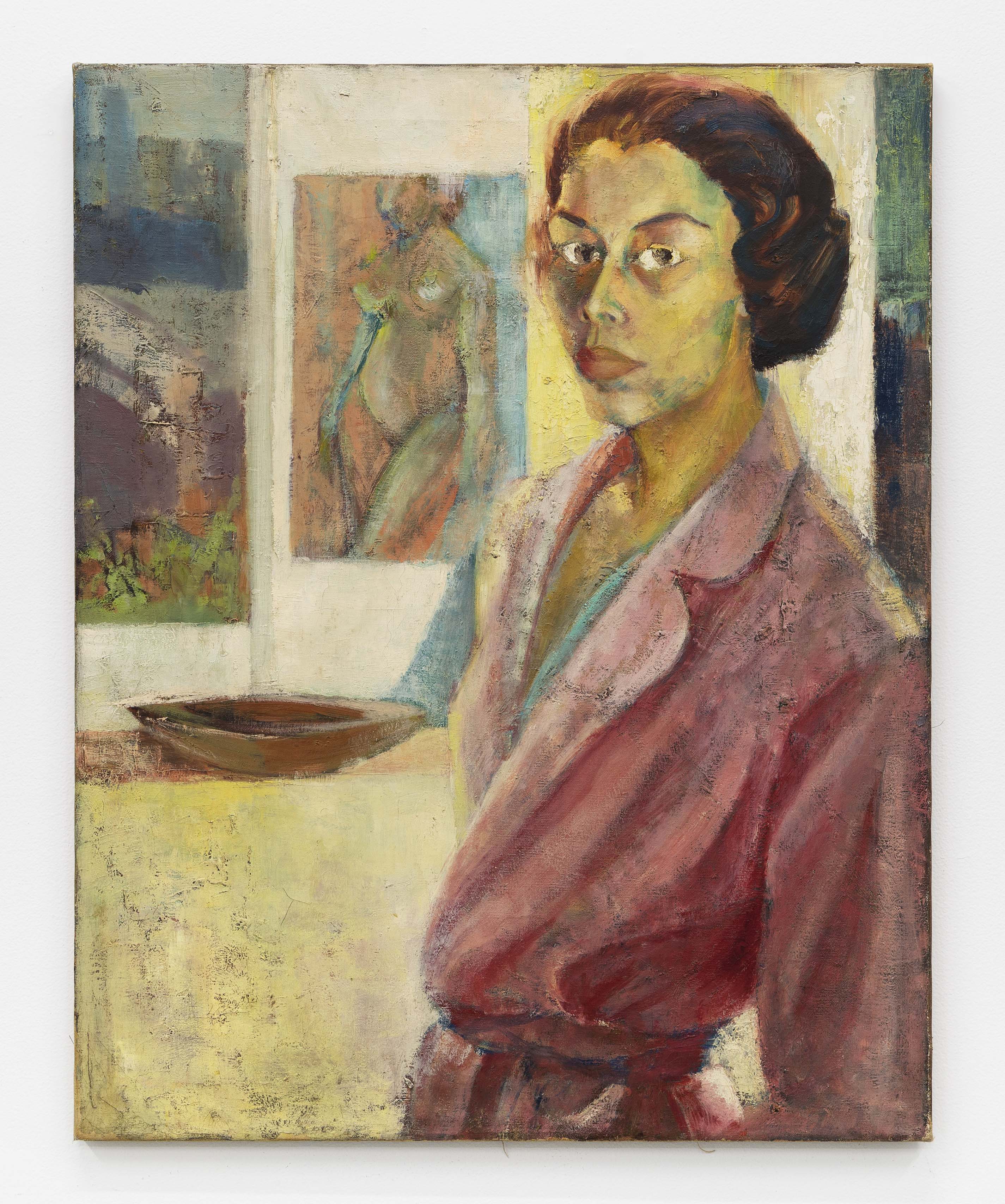

That imperative comes through in Browne’s self-portrait. Leaning against a wall in a cranberry jacket, her blouse a sliver of turquoise, she looks out stiffly, resolutely, her eyes searing white against her warm skin. Unlike the men she pictured, Browne here is cerebral, probing, nothing escaping her steely gaze. “It’s only the artist who can save people,” she said, “if only just letting them look and see.”

If you go

Vivian Browne: My Kind of Protest

Phillips Collection, 1600 21st St. NW.

phillipscollection.org

. 202-387-2151.

Dates:

Through Sept. 28.

Prices:

$20, with discounts for seniors, students and educators, military, and visitors 18 and under.