When Priscilla Chan opened a school for disadvantaged kids in 2016 with her husband, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, she took aim at some of America’s thorniest challenges.

“A persistent academic achievement gap separates white children and children of color — and wealthier children and their lower-income peers,” the school’s website said. “A similarly large health gap mirrors these differences.”

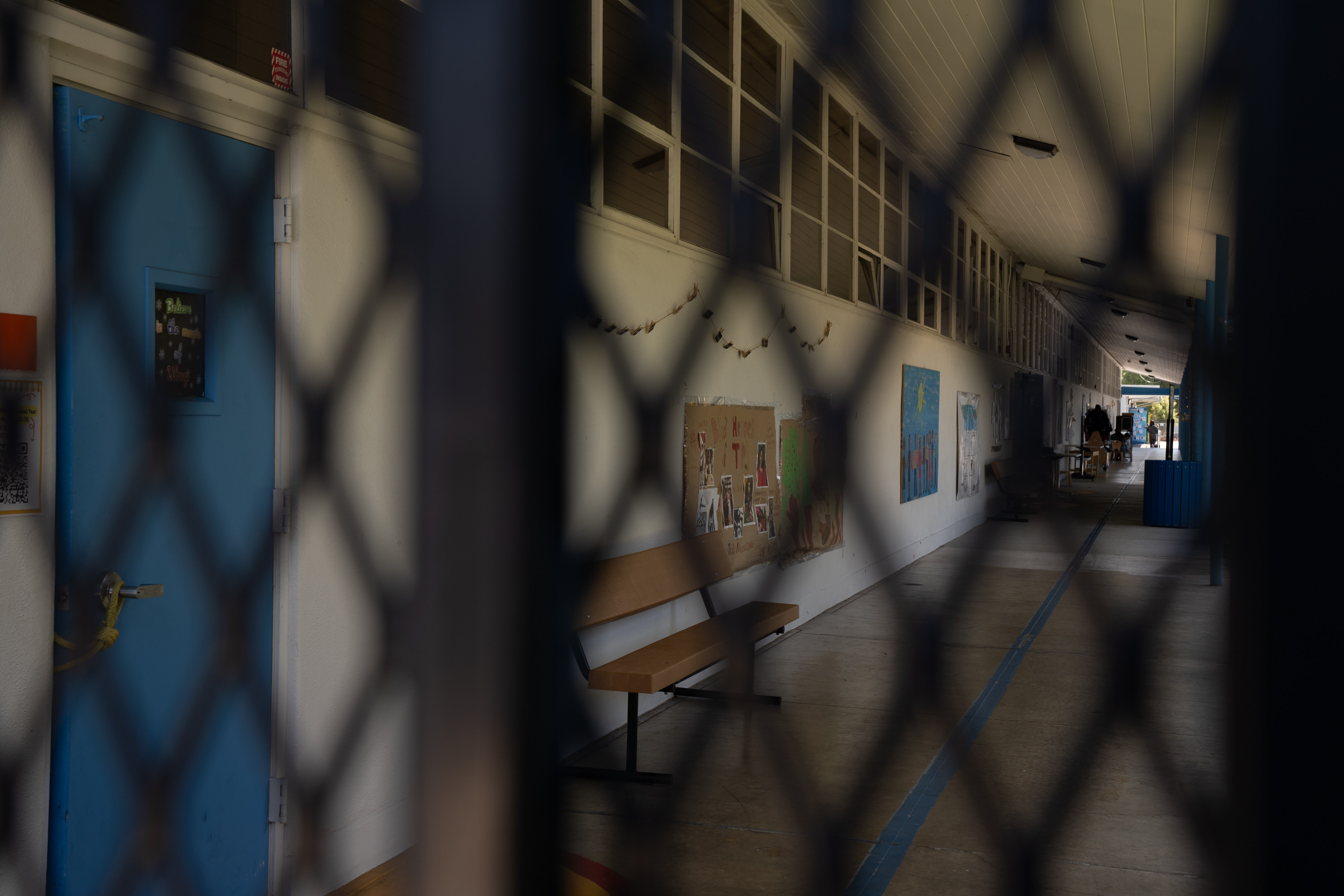

The Primary School, in East Palo Alto, California, offered free tuition, as well as free health care and counseling for students and parents, in an attempt to show that giving kids the right support could lessen those gaps. In 2018, Chan, a pediatrician, told CNN she was in for the long haul. “To really understand the full impact of your work,” she said of her school, “you’re just going to have to be patient.”

But in April, less than a decade after the Primary School opened, Chan told staff it would shutter its two locations after the 2025-2026 school year. Weeks earlier its board had voted unanimously to close because of lack of funding: The billionaire couple’s philanthropic Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the school’s sole donor, was pulling out.

Chan and CZI declined to say why the couple opted to abandon the Primary School. But former leaders of the school who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss private information said Chan had grown distant in recent years as the school’s academic performance faltered. And the closure comes as she and her husband have pivoted CZI away from projects touching on social and political issues.

The impacts of the shuttering on families and the local school district show the risks for communities that depend on wealthy donors for essential services or support. A billionaire’s change of heart can destabilize vulnerable families or local government finances.

Parents and teachers — who learned about the closing in a last-minute meeting one Thursday in April, many of them by video chat — said they were shocked. Several parents told The Washington Post that Chan has broken her promise to their children, who attend the school’s main location two miles from the campus of her husband’s company.

Nearly 90 percent of the Primary School’s roughly 400 students in preschool to eighth grade identify as Latino, Asian, Pacific Islander, Black or multiracial. At its separate preschool across San Francisco Bay, 98 percent of families have incomes that would qualify for state-subsidized tuition at a conventional school that charged fees.

Many families will probably turn to the local public school district, Ravenswood, which closed two schools around the time that the Primary School launched. At a board meeting late last month, the district’s assistant superintendent of finance, William Eger, said it will face “long-term financial pressure” because of the closure, despite CZI’s committing to cover the cost of educating any students from the Primary School through 2031. To address the shortfall after that, the district is considering turning one of its campuses into housing.

CZI declined to make Chan available for an interview. “We’re hopeful that the most successful elements of the school’s model will become accessible to more students and families through integration with the Ravenswood City School District,” communications director Jane Packer said in an email statement.

CZI has promised a parting gift totaling $50 million to the community. Parents were told students will receive $1,000 to $10,000 for their future education based on age, and the school district received $26.5 million in grant funds last month. The district declined to comment for this article.

“We’re very proud of the work we’ve done at The Primary School over the past decade, and of what our children and families have achieved,” Carson Cook, a spokesperson for the Primary School, said in an email.

Shannon Todd, a parent who has been with the Primary School since it opened, said its closure will be difficult for her family, whose three children attend the school. It provided disability testing, coaching and help navigating health care, said Todd, who has unsuccessfully pushed for Chan to meet with families.

“For her to come into our community and give us the hopes of a better future for our kids and now just pull the plug like that is not fair for these kids,” she said.

Dream school

East Palo Alto is neighbor to wealthy Silicon Valley towns like Palo Alto, where the children of employees at Google and Meta, as Zuckerberg’s company is now called, can receive top-rated public educations for free. Because of historical redlining, residents of East Palo Alto are mostly lower-income families of color. Many struggle with the region’s cost of living.

The Primary School opened in 2016 with 40 students and a “whole child” philosophy that offered free health care for students and families, plus coaching and mental health support for parents.

Chan, the daughter of refugees who fled Vietnam and settled in a low-income Boston neighborhood, hoped to prove that access to good health care and schooling could help economically disadvantaged students achieve more. “We are working toward a world where every child gets an education that gives them a fair shot,” she said in a 2019 speech.

The East Palo Alto project was the billionaire couple’s second major intervention in a city’s education system, after a controversial 2011 gift of $100 million to the Newark public schools. Some experts and community members claimed that the money was largely squandered. In 2017, a Harvard

study

funded by CZI found that by 2015 the growth rate of student achievement in English had significantly improved — but that there had been no significant change for math.

Chan’s partner on her new mission was education leader Meredith Liu, whom she hired from Boston’s Codman Academy, a model for her project. “People thought they were going to get the school of their dreams,” one former school administrator said, speaking on the condition of anonymity to protect her career. Current staffers at the Primary School were asked to sign nondisclosure agreements.

In reality, the school met stumbling blocks. Two principals left in its early years, which three former school leaders said made it difficult to establish stability for students.

The Primary School tested innovative ideas but didn’t have some standard features of many schools.

It didn’t have the special education system or disciplinary rules that are required of charter schools, the former administrator said. But students wore recording devices dubbed “speech pedometers” so that software could analyze the speech patterns of children and the adults around them. The technology was designed by a

nonprofit

to encourage staffers to talk more with students in ways that studies suggest encourage brain and language development.

“It was beyond naivete,” the former administrator said. “It was hubris.” In

annual reports

, the school credited the devices with helping staffers track and improve students’ language development.

In the Primary school’s fourth year, the coronavirus pandemic brought disruption, especially to the school’s literacy rates.

Katherine Carter, a former public school administrator brought on in 2019 to assess the Primary School’s academic struggles, was surprised to find that staffers did not use science-based

methods

to teach reading, according to a 2023 blog post on the school’s website.

“It takes three to five years of consistent leadership for a school to really take off,” the former administrator said. “And the Primary School never had that.”

In 2023, Liu — Chan’s co-founder and the school’s president — died unexpectedly. The two were close, people familiar with the school and their relationship said. According to the former administrator, Liu “was the visionary.”

The tragedy cost the Primary School its closest tie to Chan, who by then had stepped down as the board’s chair. In recent years, she has been seen at the school infrequently, three people familiar with its operations said.

Another former administrator recalled leaders of a similar school advising that it might take 20 years for the Primary School to deliver the outcomes it sought. “I remember hearing that and thinking, ‘We don’t need to be rushing … we just need to keep at it,’” the former staffer said, also speaking on the condition of anonymity for fear of damaging her career prospects.

The Primary School had been operating for only nine years when its board voted unanimously in April to close it because of the lack of funding. “Any model that leans on one primary funder is not something I’ve felt was sustainable,” board chair Jean-Claude Brizard said in an interview with The Post, although he praised the school’s work.

Cook, the Primary School spokesperson, said in an email statement that the school’s focus on literacy saw the percentage of students meeting or exceeding grade-level reading standards steadily increase.

“I don’t think it was enough time,” the former administrator said.

Wound down

CZI’s withdrawal from the Primary School came after a flurry of changes at the philanthropy in the early months of President Donald Trump’s second term. They included announcing layoffs, abandoning diversity policies and pulling out of work on community, education and social issues.

CZI had been founded alongside the start of the Primary School project in 2015 as part of Chan and Zuckerberg’s pledge to emulate Bill and Melinda Gates in giving away the majority of their wealth. Facebook’s founding couple have led CZI even as Zuckerberg continues to serve as CEO of Meta, possibly meaning their philanthropic ventures could complicate the company’s relationship with politicians and regulators.

In 2020, during Trump’s first term, Zuckerberg touted CZI’s work on racial equity after the death of George Floyd. Some employees saw the comments as tone-deaf and his philanthropic work as insufficiently ambitious, according to previous Post reporting as well as a person familiar with the matter.

The same year, the couple gave $400 million to help state and local governments run the pandemic election, but some Republicans called the donation “Zuckerbucks” and claimed it was part of an alleged scheme to favor Democrats.

Under the new Trump administration, some of CZI’s established programs could appear out of step with moves by the White House to eradicate diversity, equity and inclusion programs.

Shortly after that election, Zuckerberg and Chan began to pull CZI back from social issues. Its criminal justice reform work was spun off into a separate organization. To insiders, it seemed part of a strategy to separate the CZI name from a sensitive political topic.

CZI stopped launching new racial and criminal justice equity programs, and its immigration work moved to

FWD.US

, an advocacy group that supports expanding immigration.

After Trump’s reelection last year,

Zuckerberg reversed

some of his previously stated positions on diversity and content moderation,

ending

Meta’s fact-checking programs and many of its

diversity initiatives

.

In parallel, more changes came to CZI, which laid off members of its community team that worked on affordable housing, supported local civil society groups and helped underrepresented entrepreneurs. Days after it publicly confirmed that the Primary School would close, it emerged that the philanthropy was also ending its statewide housing program, which studied housing policy and tried to

spur production

of affordable homes.

“As we’ve focused on science, we’ve wound down our social advocacy funding,” Chief Operating Officer Marc Malandro

wrote in a February email

to CZI staff, in favor of “pushing the frontiers of biology and AI.”

In an email statement, Packer, CZI’s director of communications, said the initiative was focused on “building technology to help scientists unlock a deeper understanding of how the human body works,” which she said “has been a core mission since our earliest days.”

‘Tremendous impact’

Gisselle Munoz, a 24-year-old mom, attended public school in Ravenswood. She was excited to offer her kids, ages 3 and 4, something better at the Primary School.

In April, when parents were asked to attend an important meeting, she joined via Zoom and heard staffers announce that the school would close. Some parents were so shocked and angry that they hung up, she said.

The school’s closure “stresses me out,” Munoz said. “We have to find another school and start all over again.”

At the meeting, a presentation said each family would be allocated a “transition specialist” to help them choose a new school and detailed the education savings money students would receive: $10,000 for elementary and middle school students, $2,500 for preschoolers and $1,000 for younger kids.

“We understand that this news has a tremendous impact on your family,” read a copy viewed by The Post. Some parents said in interviews that the money promised to their children felt insignificant compared with the costs ahead.

CZI’s Packer said in an email, “We’re hopeful that the most successful elements of the school’s model will become accessible to more students and families through integration with the Ravenswood City School District, building on its strong foundation in health programming and parent engagement.”

Kyra Brown is a fourth-generation East Palo Alto resident and activist who has written about displacement and gentrification caused by the tech industry. She has long been skeptical of allowing the community to become dependent on billionaires like Zuckerberg.

“People can promise stuff all day long,” Brown said, but “if nothing is legally binding, they’re going to pull out, and we’re going to be left with the fallout.”

When the political climate changed under Trump, Brown surmised, so did the Chan-Zuckerberg commitment to East Palo Alto.

Munoz, the young mom, said she saw news outlets reporting that the closure of her daughters’ school was related to Trump, but was unsure.

“I don’t really get into that politics stuff,” she said. “I’m too busy trying to survive.”