As Nigeria joined the global community in marking World Milk Day on June 2, the celebration came not with a glass brimming with local milk, but with a sobering reality: we want milk, but it is simply not available.

In his remarks at the commemoration ceremony in Abuja, Alhaji Idi Mukhtar Maiha, the Minister of Livestock Development, captured the national sentiment succinctly: ‘Everybody wants milk, but it is simply not available.’ His words echoed the frustrations of families, nutritionists, and stakeholders who see the growing gap between demand and supply in Nigeria’s dairy sector.

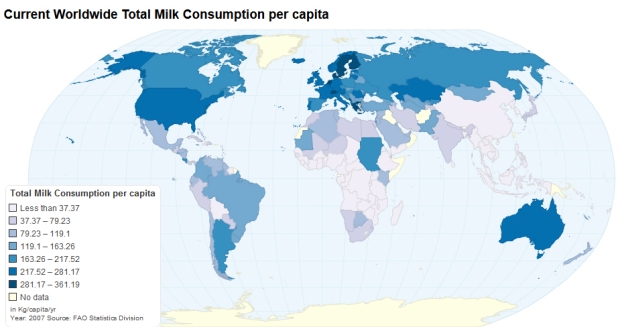

According to available data, Nigeria’s average per capita milk consumption stands at approximately 8.1 litres per annum – a stark contrast to the global average of about 44 litres. In developed economies such as the United States or the European Union, that figure rises to over 200 litres. The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) recommends at least 210 litres per person annually for optimal nutrition. By this standard, Nigeria falls woefully short.

This consumption gap is not merely a matter of personal dietary choice; it reflects a structural failure within our dairy industry and broader livestock value chain. Despite having one of the largest cattle populations in Africa – estimated at over 20 million – Nigeria remains heavily dependent on dairy imports, spending close to $1.5 billion annually to bridge the shortfall. Yet, even these imports are insufficient to meet the country’s nutritional needs. Several factors might have contributed to Nigeria’s dairy dilemma.

Our milk production system remains predominantly traditional and low-yielding. Most of our cattle are indigenous breeds that produce less than two litres of milk per day, compared to exotic dairy breeds that can yield 20 litres or more daily under proper management. Furthermore, over 90 per cent of dairy production is controlled by pastoralists using age-old, extensive systems with minimal access to feed supplements, extension services or veterinary care, There is also lack of critical infrastructure – poor roads, cold chain logistics, and absence of milk collection centres mean that even where milk is produced, a large portion is lost before it ever reaches the market. Processing plants operate below capacity or rely heavily on imported powdered milk due to an insufficient local supply.

The industry is poorly coordinated. Unlike other agricultural sub-sectors that have begun to benefit from public-private partnerships, donor interventions, and enabling policies, dairy development in Nigeria is suffering from fragmented efforts, policy inconsistency, and inadequate investment.

The consequences of this neglect go beyond economics. Malnutrition remains a silent epidemic in Nigeria, particularly among children under five. Absence of milk (rich in protein, calcium, and essential micronutrients crucial for child growth and development) in the diet of millions of Nigerian children contributes significantly to stunting, poor cognitive development, and weakened immunity.

Women, too, bear the brunt of this crisis. As primary caregivers, they often sacrifice nutritious foods for their children, compounding the problem of maternal malnutrition, especially in rural communities.

The good news is that change is possible – and increasingly urgent. To transform our dairy sector into a viable, nutrition-sensitive, and inclusive economic driver, we should invest and embrace breed improvement and genetic upgrading programmes to replace or cross indigenous cattle with higher-yielding dairy breeds. The government should back and support artificial insemination (AI) programmes, followed by livestock extension to raise milk yields significantly within a few years.

The new ministry should facilitate the establishment of Dairy Clusters and Milk Collection Centres as ‘dairy hubs’ or clusters – where producers, processors, service providers, and buyers are co-located – this has proven successful in countries like Kenya and India. These hubs should be supported with milk collection centres equipped with chilling tanks, veterinary services, feed mills, and transport links.

The pastoralists must not be excluded from this modernisation agenda. Incentives for voluntary settlement, pasture development, and inclusion in formal dairy cooperatives can help integrate these traditional producers into the modern economy while reducing conflict over land and water.

Government alone cannot solve the dairy problem. The private sector should be incentivised through tax waivers, access to credit, and import substitution guarantees to invest in dairy processing, cold storage, and breeding programmes. Notable examples already exist, such as FrieslandCampina WAMCO’s Dairy Development Programme in Oyo State.

Government should stimulate demand through the School Milk Programme for nutritional impact as practiced in India and Brazil. This can have a dual effect: improving child nutrition and creating steady demand that justifies investment in local milk production. If well-managed and locally sourced, this programme can transform the dairy landscape.

Nigeria’s agricultural research institutions can be repositioned to train and build the capacity of dairy producers as well as support dairy research, including feed formulation, breed adaptation, and value addition. Training of dairy extension officers and veterinary professionals should be prioritised, especially under the new Ministry of Livestock Development.

While Nigeria has already launched a National Dairy Policy, implementation has been slow. The new ministry must prioritise this policy as a cornerstone of livestock sector reform, ensuring it is backed by funding, legislation, and strong monitoring frameworks.

As we marked World Milk Day, Nigeria stands at a crossroads. We can continue to bemoan the scarcity of milk while spending billions on imports, or we can seize the opportunity to invest in a modern, resilient, and inclusive dairy industry. The dream of milk in every Nigerian home is not naïve. It is achievable – with the right focus, the right investment, and the right leadership.

The creation of the Ministry of Livestock Development offers a fresh chance to reset the narrative. But that chance will only bear fruit if backed by bold policies, political will, and multi-stakeholder collaboration. Milk must no longer be a luxury item or an import statistic – it must become a nutritional right and a driver of rural prosperity if we want to celebrate the power of dairy in Nigeria.

Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (

Syndigate.info

).