Aeroplane

air health primarily concerns the quality, safety, and potential health impacts of the air that passengers and crew breathe during flights.

This essay is targeted mainly at the increasing number of Nigerians who see air travel as both a necessity in the modern world and an extra layer of personal safety in an increasingly unsafe environment, especially with the rising level of insecurity in various parts of Nigeria.

Support kami, ada hadiah spesial untuk anda.

Klik di sini: https://indonesiacrowd.com/support-bonus/

While road travel is the only means by which most people classified as poor can commute from one point to another, it is often also the most economical means by which cargo and other forms of economic engagement can be realised.

Road travel, therefore, is one means of human mobility that can never entirely be replaced by air transportation.

However, the major theme of this week’s essay remains the quality of the air that passengers and airline crews breathe in the course of travelling, whether on short-haul flights or major international routes.

Support us — there's a special gift for you.

Click here: https://indonesiacrowd.com/support-bonus/

It is also an issue that has gained much prominence in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic and the lesser pandemics of the Ebola virus disease and Marburg fever.

Today, with concerns about the resurgence of measles in many advanced countries, this is an issue of rising concern, which we also discussed on this page last week.

It is certain to continue raising both concerns and awareness in the coming years.

Key aspects of these efforts to mitigate the risks posed by the quality of air people breathe inside a closed aluminium tube hurtling through the air at high speed include the following major components, which we shall examine comprehensively.

To begin with, air filtration and ventilation must be seen as the most critical aspects of this effort to control the quality of air on board an aircraft. It is irrelevant whether the aircraft is a small air ambulance, a jumbo jet, or even a helicopter; the principles are the same. Modern commercial aircraft, our focus in this essay, as they are mainly used for transporting both humans and goods, are the items of utmost concern today.

These planes use High Efficiency Particulate Air filters that capture a remarkable 99.97 per cent of particles larger than 0.3 microns floating in the cabin atmosphere, including viruses and bacteria, similar to hospital operating rooms.

With this method, cabin air is refreshed 20–30 times per hour, which is equivalent to every two to three minutes, with a mix of 50 per cent HEPA-filtered air and 50 per cent fresh air from outside the plane.

This reflects the nature of air-conditioning that is operational in such aircraft. The airflow is designed to move from top to bottom, thereby minimising the horizontal spread of contaminants and microbes.

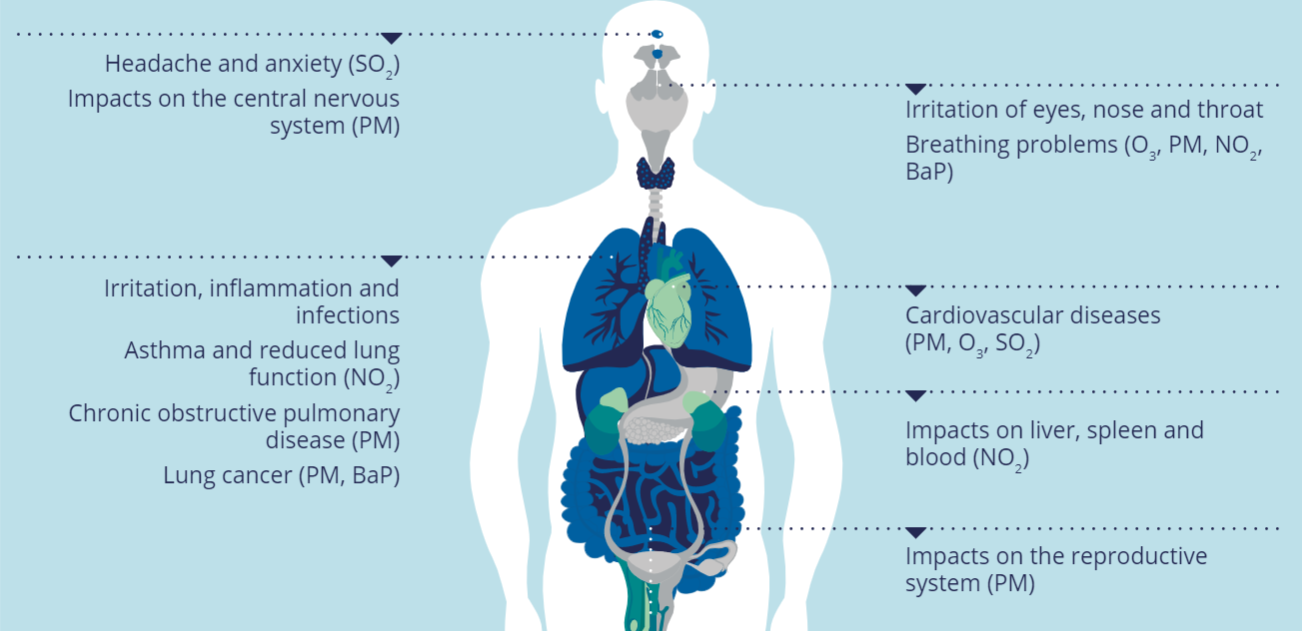

Risks of air contamination can also arise from certain rare incidents where engine oil or hydraulic fluids containing toxic organophosphates, volatile organic compounds, and ultrafine particles leak into the cabin’s air supply from the air pocket surrounding the plane. These can cause acute symptoms such as dizziness, respiratory problems, and potential long-term neurological effects, especially for frequent flyers like crew members.

Older planes, such as those more than 20 years old, may lack HEPA filters and therefore, rely on less effective systems.

Ground operations involving boarding and takeoff pose higher risks due to reduced airflow into the cabin before the filters engage.

Airborne diseases such as COVID-19 and influenza can spread in this kind of environment, but studies have shown that the risk is lower than in offices or classrooms due to HEPA filtration and rapid air exchange. Close proximity to infected passengers remains a concern, especially during long flights.

This is why many countries are now enforcing more stringent health check regulations before passengers from certain other countries are allowed through their borders.

These are regulations which airlines are obliged to enforce, but there are gaps in such systems, especially when certain passengers carrying a variety of potential infections are still in the early stages of their respective infections at the time of travel.

In this connection, we must remember how the late Liberian diplomat, Patrick Sawyer, brought Ebola with him into Nigeria.

There are other health concerns, of course, particularly with respect to low levels of humidity within an aircraft cabin, which is usually around 6 per cent and can cause dehydration and discomfort, although it does not directly harm our health.

This makes frequent hydration efforts important during air travel, especially on major international routes.

Then there is the risk of cosmic radiation. Exposure is minimal for occasional flyers but may concern frequent travellers such as airline crew, although it is also emphasised that the levels remain below hazardous thresholds.

Ultrafine particles, particularly those arising from airport pollution near runways, may impact communities on the ground who live around the airport, though cabin air is less affected by these concerns.

Research on ultrafine particle pollution from certain airports has linked aircraft emissions to health risks such as preterm births and respiratory diseases for nearby residents.

This has spurred calls for cleaner aviation technologies, indirectly elevating cabin air quality standards.

In efforts to mitigate these risks, wearing masks can help reduce droplet transmission, especially during high-risk phases involving boarding and disembarking.

Airlines enforced cleaning protocols, such as the use of electrostatic disinfectants for high-touch surfaces, and passenger screening, including temperature checks, particularly during the recovery period after COVID-19.

The increasing importance of aeroplane air health is driven by several factors, including heightened public health awareness, technological advancements, and evolving travel demands.

In this section, we shall examine a detailed breakdown of why this issue has gained prominence.

The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the risks of airborne transmission in enclosed spaces, including aircraft cabins. While studies show that modern cabin ventilation systems with HEPA filters, refreshing the air 20–30 times per hour, help to reduce transmission risks, travellers and regulators now prioritise air quality as a critical safety metric.

Airlines, particularly those operating in Southeast Asia, have adopted enhanced protocols such as masking during high-risk periods and promoting rapid testing to address lingering concerns about respiratory illnesses like COVID-19 and influenza.

Research by Airbus, Boeing, and Embraer confirms that cabin airflow designs, such as top-to-bottom circulation, limit droplet spread more effectively than typical indoor spaces, including offices, where less attention is paid to airflow patterns.

Some airlines now integrate air quality sensors to track particulate levels, thereby boosting passenger confidence.

Studies by the Harvard School of Public Health and the U.S. Department of Defense validate aircraft ventilation as being superior to that of many buildings. Travellers increasingly choose airlines based on health and safety ratings.

Organisations such as the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration, the International Air Transport Association, and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have updated guidelines emphasising air quality.

These organisations highlight the role of HEPA filters and high air exchange rates in reducing infection risks.

For instance, airlines now advertise HEPA filtration and air renewal rates as selling points. Luxury cabin upgrades, such as Air France’s La Première, now include air purity as a key feature.

These developments are important in combating emerging health threats, such as a quartet of transmissible diseases like COVID-19, influenza, respiratory syncytial virus, and norovirus—dubbed the “quad-demic” in 2025.

This convergence of infections has reinforced the need for robust cabin air systems to mitigate the risk of simultaneous outbreaks during travel.

Airports and airlines now treat air health as part of broader biosecurity measures.

However, these efforts have not consistently eliminated the risks associated with air travel. Aeroplane air health is now a multidisciplinary priority, balancing infection control, passenger trust, regulatory compliance, and environmental impact.

Innovations like HEPA filters and laminar airflow, combined with post-pandemic vigilance, ensure it remains central to the future of aviation.

Although aeroplane air is generally cleaner than that in most indoor spaces due to advanced filtration, risks remain, such as fume events, infection from nearby passengers, and low humidity.

For most travellers, the greatest health threats are touching contaminated surfaces or sitting near ill passengers, not the air itself.

Provided by SyndiGate Media Inc. (

Syndigate.info

).